The Overwritten City

Sean Pyestock

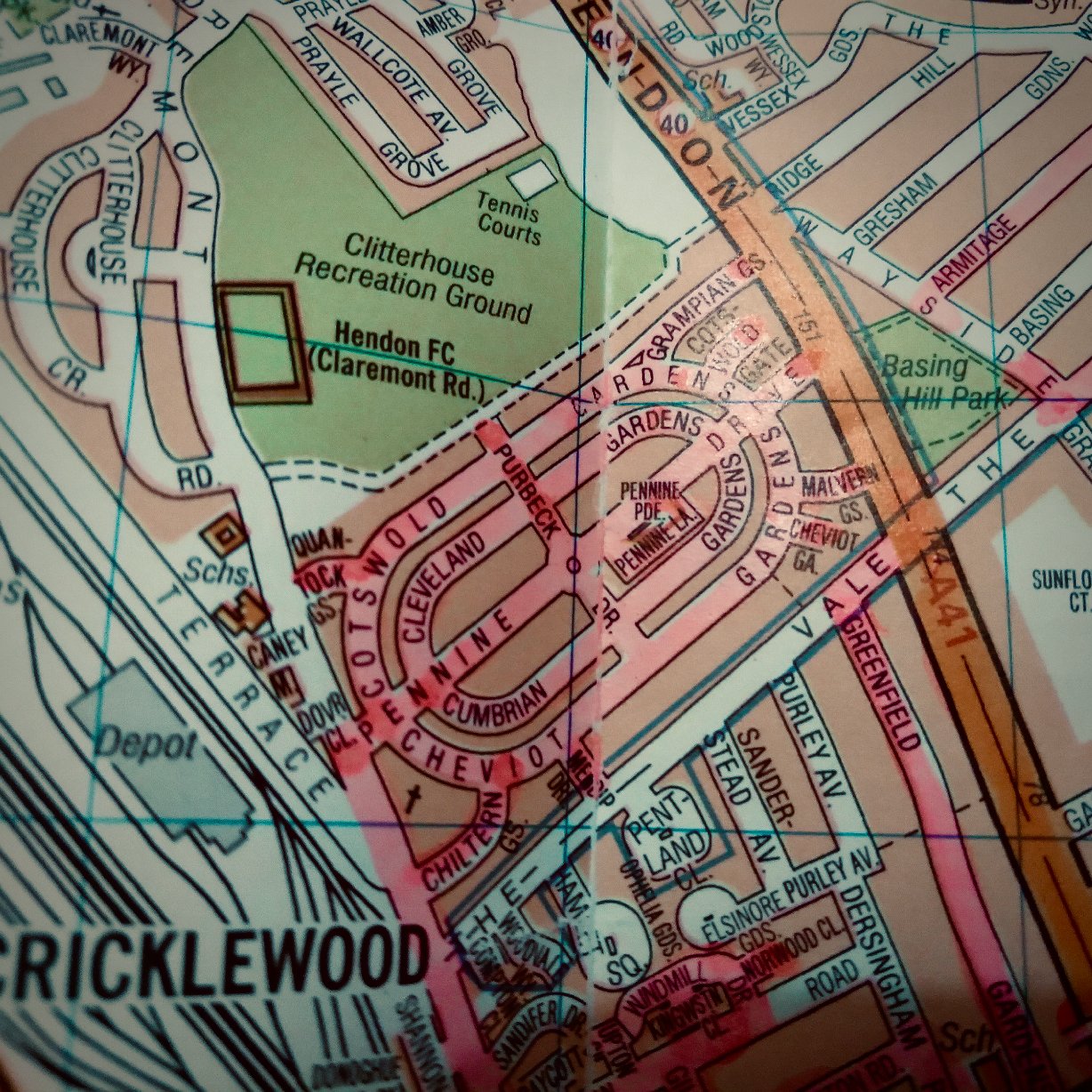

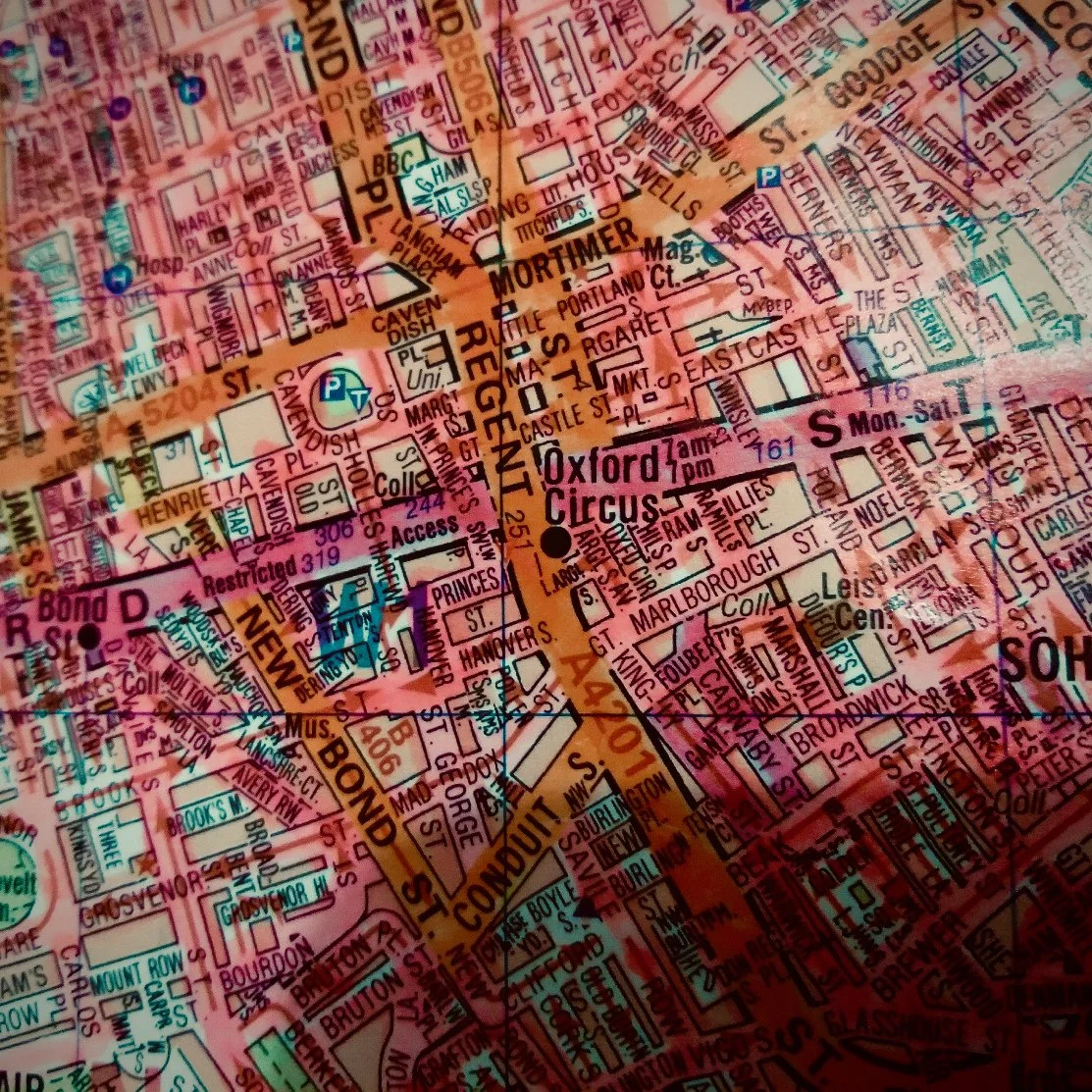

This is my A-Z streetmap of London, coloured in with pink marker pen to show all the streets I've ever been down in the city (walking, running, cycling, bus, car, whatever). I'm a runner, so that helps. On a long run I can cover a chunk of streets, although that's not as fun as a long linear route. Sometimes I set out to do a specific area, though I've been a bit slack about that lately. It's not something I'm obsessed about and sometimes I forget about it for weeks.

I've had the map on the go for maybe four or five years. North and central London is pretty pink, everywhere else is a bit empty. It's not a perfect record. There are huge parts that I haven't coloured in yet, although I used to live south of the river and roamed over quite a lot of that area. The trouble is I can't remember exactly which roads I've been down and which I haven't, so I can't colour them in. One exception is the roads I had to cover when I was retuning videos for the launch of Channel 5. If anyone lived in Streatham in 1996/97 and I broke their television I apologise, but they can find some solace in knowing that their street is etched on my memory for ever.

If I put my mind to it I'd be able to add a few extra streets here and there from distant memory. I've run the London Marathon a couple of times and haven't even added the roads from the route, which is an open goal.

Basically, every road counts – not paths or alleys etc – unless it's gated and locked off (though if it's open I may well have a snoop). I haven't coloured in parks – unless they have a road going through them, of course.

It's not an original idea: there may be dozens of folk all over the city doing a similar thing. A character in Geoff Nicholson's novel Bleeding London had an A-Z on the go. I suspect some people are doing it digitally, which isn't my bag, though I do sometimes get a bit of GPS assistance with my memory.

I think Google Maps is a disgrace – just so ugly. It serves a purpose, of course, but it looks like it was designed without any input from a cartographer. Half the time you can't even find a scale. OpenStreetMap is much more respectable and can be brilliant for finding your way by foot in murky corners. Needless to say OS maps are the gold standard – but for this project it has to be a proper street map.

The map itself is the classic foldout A-Z covering 6 miles around Charing Cross. The map defines the limit. If it's not on the map, I'm not going in. I like maps but I can't say I feel any special affection for this one, though it's very much fit for purpose. It's pretty knackered at the folds now, which does upset me a little bit – a north-south fault line has opened up between Hornsey Road and Copenhagen Street (precisely mirrored between Clapham Road and the South Circular, of course).

The need to cover more streets means there's a bit of a tension between me and the map – am I choosing where to go or is it choosing for me? Running up and down (and across) a grid of streets in Hendon is not everyone's idea of a good day out, though it's surprising what turns up. Everywhere's interesting. Certain things become obvious targets – such as the Cricklewood Ovals (that's my name for those streets) pictured here.

Anyway, I've never really thought about this in detail before. It's just a thing I do. But clearly it's about completism (though I don't expect completion) – and control. There's a big mass of city out there and I can't see it all, I can't understand it, I can't fathom the point of it (beyond it being a functional machine to allegedly help humanity to grind out an existence of course). I get the same feeling with the view from the top of a mountain – I could stay up there and look at it all day, but what's it for? How does it work? What's it got to do with me? Why can't I absorb it all? It's selfish really. I usually come off summits with a tiny sense of loss. It's a little different in that generally I value and enjoy the view from a mountaintop more than the city.

Section editor's note

I asked Sean Pyestock to write about his altered London streetmap as an example of how a non-specialist can transform a mass-produced commercial map into a many-layered artefact that is used to both record a personal history and to spur their further adventures. Sean is not an artist, a cartographer or a proponent of psychogeography, he simply finds satisfaction in making a record of his paths through the city.

Sean's map is very different from the book version of the A-Z in the Geoff Nicholson novel[1] he mentions, in which the streets walked have been written over with thick black lines. The streets on Sean's wall map are literally illuminated by fluorescent pink marker pen – a small but critical difference. The map described by Nicholson has become “an absurd puzzle, a conundrum, a maze”, the markings “reduced to a pattern, to decoration and ornament”, “as if the whole of London has been scored through and obliterated”. In contrast, Sean's markings leave the street names visible and draw attention to his relationship with those streets, the opposite of the “theoretical and anonymous” city in Bleeding London. His intervention overwrites the familiar design with his experience and makes it into something completely individual, a tool for mastering the city, inscribed with his physical actions and memories and a long way from the abstract representation it is designed to be.

Sean Pyestock is a keen explorer of London. He works in publishing.

Notes

[1] Bleeding London by Geoff Nicholson, first published in 1997 by Harbour Press