Ground Work

Rosie Hallam

Abstract

Through the act of walking and visually recording I have created an affective, multi-layered sensorial ‘map’ documenting the King’s Cross Development and the Islington ward of Caledonian that it borders with. By being, seeing, feeling there, this paper will reflect on how space is reimagined, produced, and lived in, both outside and within hyper-gentrified zones whose over-arching purpose is the commodification of space and the maximisation of land value. Thinking about space and time referencing the writings of Lefebvre and Massey, through the embodied act of moving through different places, I will witness, compare, and report on how Tabula Rasa developments such as King’s Cross fit with the ability of space to be relational, a sphere of possibility, a social product and always in the making.

Introduction

The King’s Cross Development in North London is a 67-acre, £2.2bn redevelopment project and the largest inner-city regeneration in Europe.[1] The development consists of the square at King’s Cross station along with retail, work, culture, educational and living units that have been built to the north of the station around several parks and squares available for use by the public. The site has been implanted into an area that previously consisted of disused former Victorian industrial units, independent businesses, charities, shops, and social housing.

I will examine the effects that commodification, sanitisation, and securitisation have on how space is realised in hyper-gentrified spaces in comparison to the traditional built environment adjacent to this site that has grown and changed over centuries.

Moving through these two distinct spaces - from old to new - this paper will highlight the often-subtle clues that distinguish Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) from public highways and open spaces. Said clues reference the material: signage, maps, security devices, paving stones, as much as the natural: security guards and cleaning teams. I will investigate the narrative according to which although privately owned public spaces are cleaner and seemingly safer, this can be at the expense of inclusivity and the capacity for people to have real and creative encounters and experiences.

Following on from the observational writings of Walter Benjamin who, in the early 20th Century, used flânerie as a way of confronting the ever-changing dynamics of the city, I use walking as a means of affording me the opportunity to embed myself into my research. It allows me to viscerally experience and reflect on real lives and lived experiences as I witness them.

Through personal narrative and ethnographic detail, walking enables me to make sense of the academic research that runs in tandem. By reflecting on the work of Philosophers such as Michel De Certeau who noted that ‘history begins at ground level with footsteps’[2] and Sociologists such as Georg Simmel who theorized on the significance of space, stating that there were five sociologically significant characteristics of space: ‘exclusivity, divisibility, fixity, proximity and mobility’,[3] I will be evaluating the development at King's Cross as a representation, in microcosm, of the wider processes of gentrification affecting cities and societies globally.

Ground Level

I begin my journey on a grey December morning, leaving home armed with a small camera, notebook, pen and a 1980’s fold-out London map to help me envisage King’s Cross prior to development.

I take the Overground the five stops from my home in Homerton to Caledonian Road and Barnsbury Overground Station from where I will walk one mile through the Islington ward of Caledonia to the eastern edge of King’s Cross, continue through the site to the western edge before heading south to King’s Cross Station, around the station, up York Way and back to Caledonian Road and Barnsbury Overground. A journey of approximately 6 km. I will be paying particular attention to how these two neighbouring areas of the Islington ward of Caledonian and the development at King’s Cross speak to the notion of the encounter and to the idea of a multitude of layered and overlapping stories.

Although a photographer and an urbanist, I have mostly learnt the skill of observation from the works of nature writers. Nan Shephard, who spent a lifetime walking in the Cairngorms and wrote about those visits in her seminal book, The Living Mountain described herself as being a ‘peerer into corners’.[4] For her, it was never about looking up at the peaks. From her I have learnt how to look at and understand the smaller details.

I walk south along Caledonian Road - known locally as ‘Cally’ Road - in the direction of King’s Cross. I am taken by how little has changed on this road over the years. There are none of the obvious signs of the creeping gentrification taking hold in other parts of the city. No proliferation of boutiques and artisan shops, bakeries selling Sourdough bread at £6 per loaf or coffee roasteries replacing the all-day cafes.

Observing the shops and other material objects gives me a sense of the demographic mix that makes up the area. Lycamobile posters in Romanian and Polish plaster empty shop fronts in between Turkish Cafes, a Chinese Supermarket and Burger Bars. There’s also a shop specialising in the sale of Watermelons although no one I ask can ever remember it being open.

Material clue to ethnic mix of the area

Dallas Burger Bar where the chef’s special is £10.95

Ocean Chinese Supermarket open seven days a week

No one I ask can remember when this shop was last open for business

Men sip coffee outside Kigi Cafe as they watch the world go by

When I check the Office for National Statistics [5] to get an understanding of the makeup of Caledonian Road, it has a broad range of ethnicities typical of inner-city London in 2020.

Crystal Roof, 2021a

There is a general air of deprivation and under-investment. Fly tipping is in evidence and there are several long-boarded up shops

Boarded up shops show signs of under investment

Cally Pound Plus Ltd - Open 7 day a week, this is one of the many ‘useful’ shops on Caledonian Road.

Fly tipping remains uncollected

Weapons amnesty box

I witness a busy road full of people moving with a sense of purpose. Shops run the length of both sides of the road and are include supermarkets, corner shops, butchers, bakers, cafes, nail parlours, barbers and an assortment of hardware stores. Apart from a Costa Coffee and Co-Op and Iceland supermarkets, there are none of the other chain stores typically found on many high streets in Britain.

Further along, a weapons amnesty box stands on the corner of Caledonian Road and Stanmore Street. Sponsored by weapons surrender charity word 4 weapons, they supply knife bins to police forces, community groups and faith organisations.[6] This is the first time I have come across one of these boxes.

I photograph it and move on, stopping less than 100 metres further along. In an alcove along the exterior wall of Cally Pool and Gym, a painted white bike leans against the wall with the faded face of a teenager peering out from a photograph. The name A L A N is spelt out in plastic flowers along the floor. Painted white bikes, known as ghost bikes ‘are small and somber memorials for bicyclists who are killed or hit on the street. [....] They serve as reminders of the tragedy that took place on an otherwise anonymous street corner, and as quiet statements in support of cyclists' right to safe travel.’[7]

A material reminder of a life lost

Alan Cartwright, aged 15, was cycling along Caledonian Road in February 2015 when a young man ran out from between the cars and stabbed him to steal his bike. He died at the scene.[8] This immediately brings back a hazy memory of grainy footage from a CCTV camera on the local news at the time. It showed the exact moment this inexplicable and pointless killing happened. I was reminded of this young man whose name I had long forgotten. In more sombre mood I carry on to Bus Stop N. From here you can catch buses north to Crouch End, Archway and Edmonton Green. Two posters stuck to the glass have been partially erased and it takes a minute to decipher what they say:

‘Can’t live on 150k? Try choosing between Food and a Bus Fare Save the Zip.’

‘Economically, Environmentally and Ethically WRONG.’

Political posters are a democratic and low-cost way of disrupting discourse, and I am heartened to see these two posters plastered on to the bus stop window. They are protesting a recent Conservative decision to scrap the Zip Oyster Card as part of a £1.6 billion bailout for Transport for London. Zip Cards are for people in London under the age of 18 and offer free travel on buses and reduced fares on the Underground and Overground. They give young people a freedom that might otherwise be unaffordable. I wonder who put them up and who was so keen to remove them.

Representation space lived on at Bus Stop N

Henri Lefebvre believed that space was a social product that works on three interconnected levels. One of these was representational space, described as the space of inhabitants and users. It overlays physical space, making symbolic use of its objects.[9] The posters on bus stop N are a material expression of representational space as one of protest.

100 metres further on is Orkney House where, standing proudly out front is a wooden sculpture roughly the size and shape of a porta-loo. I can’t find out who commissioned or made it, but it has all the hallmarks of local community involvement.

I wonder who made this

I follow the Caledonian Road to where it intersects with Copenhagen Street and turn right towards King’s Cross. I stop at a faded and peeling mural on the side wall at the entrance to Edward Square. Built in 1853 the square was one of the first London gardens to open to the public. Over one hundred years later, in a state of disrepair it was saved from development into offices and flats by local community activists including Lisa Pontecorvo (who returns in this essay). Through their vision and hard work, it is now a play park and garden.

The mural at the entrance to the square was painted in 1984 celebrating the 150th anniversary of a gathering in nearby Copenhagen Fields in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs who had been sentenced to transportation to Australia for forming a trade union. Author Walter Thornbury provided the following description of the event: ‘an immense number of persons of the trades’ unions assembled in the Fields, to form part of a procession of 40,000 men to Whitehall to present an address to his Majesty, signed by 260,000 unionists on behalf of their colleagues who had been convicted at Dorchester for administering illegal oaths.’[10]

Two sections of the mural on the side of a former pub, at the entrance to Edward Square

When researching the mural, I found out it was painted by Dave Bangs who spent several years as a muralist for Community Service Volunteers Islington. Bangs speaks about murals as being ‘a form of public art on an architectural scale on which you could make large clear statements [....] was non-commercial, didn’t create commodities and was of service to people and [had] a broad appeal.’ In a recorded interview he speaks about the sociability of working on the street and of how, when painting the Tolpuddle Martyr’s mural, he would photograph people who passed by and incorporate them into the mural. ‘Our paintings were inputting a missing element into the built environment. [....] We were able to say look, you can have really good, complex, multi-layered imagery [....] which have harmonious meanings for the community [and] that tie in with their concerns.’ During the painting of the mural ‘there were endless streams of people chatting away with us, I loved all that, one of the huge pleasures [was] to know the people in the area.’[11] Ironically, In the 1990’s the mural was covered by an advertising hoarding and was only removed when Lisa Pontecorvo led a campaign for its removal.[12]

Lisa was knocked off her bike and killed on the Holloway Road in 2008. In her obituary in The Guardian Newspaper, Judith Martin wrote that Lisa fought to ‘humanise the plans for King’s Cross Central where [we] lost a large amount of historic and architecturally significant affordable housing. Lisa was justly angry. Her sense of injustice was remarkable, her social and political instincts always right.’[13]

Lisa’s portrait was painted into the Tolpuddle Martyr’s mural shortly after her death in memory to all the work she did for the community. It felt as if somehow a full circle had been completed.

Portrait of Lisa Pontecorvo (far right) in the mural

Alongside ‘representational space’, Lefebvre also talked of ‘spatial practice.’ By this he meant the relationship between daily and urban reality and the routes and networks we use that connect the places we use for work, ‘private’ life, and leisure.'[14] Looking at the mural, what it commemorates, how it came in to being and who was involved, I witness the intricately weaving together of both representational space and spatial practice. I am also reminded of Doreen Massey who said that ‘For me, places are articulations of natural and social relations, relations that are not fully contained within the place itself. So first, places are not closed or bounded [and] second, places are not ‘given’ – they are always in open-ended process. They are in that sense ‘events’. Third, they and their identity will always be contested.[15] Nothing seems truer in this small part of North London where battles have been fought and continue to be fought for the right to space.

All that I had so far witnessed on this short walk from the Overground Station to Edward Square on Copenhagen Street reinforced the idea that space is ‘constantly being interpreted and used in ways that defy its original conception.’[16] Within a stretch of a few hundred metres I had encountered many overlapping and intertwined stories. Massey spoke of space ‘as that dimension of the world in which we live,’ and reminded us that it is not just ‘a flat surface across which we walk [but that] you’re cutting across a myriad of stories going on.’[17] Stories such as the weapons amnesty box, which may have been placed on this corner as a direct result of the killing of Alan Cartwright whose memorial is a material reminder of this young man murdered for his bike. The desecrated political posters speak to the current economic turmoil and of the effects that decisions made by politicians have on individuals and their ability to be independent. And finally, this mural to the Tolpuddle Martyrs celebrating trade union movements and the individuals who stood up for worker’s rights. Massey writes of space ‘as the product of interrelations; as constituted through interactions, from the immensity of the global to the intimately tiny.’[18] I sense this as I think about the layer upon layer of stories of people and places, all laid out in front of me as I stand looking at this mural with the portrait of Lisa Pontecorvo.

By really looking into the corners, this seemingly unremarkable space represents, in microcosm, how the history of places within cities can be so contested, multi-layered, and nuanced. It speaks to this notion of urban space as a place of chance encounter, political action, and social change. ‘So instead of space being this flat surface it’s like a pincushion of a million stories: if you stop at any point in that walk there will be a house with a story.’[19]

I leave the tranquility and history of Edward Square and keep moving west along Copenhagen Street. This end of the road as it meets York Way is lined with a mixture of private and social housing. I can already make out the gleaming metal and glass architecture with its mass of leggy cantilevered cranes at the end of the road that will soon mark my arrival at King’s Cross.

I linger at the junction with York Way. On the left is a familiar row of shops I remember from years back: London Kebab, Super Laundry, Express Food Store and Café Express. I am standing in a small garden

between the shops and York Way and notice the ground studded with the metal tops of beer bottles and an overflowing bin, all material signs of how the space is used. There are no benches which I assume is a council tactic to prevent loitering. With a stubborn resourcefulness, a few people sit on the low concrete rims that demarcate the path from the bushes.

Material signs of how this space is used.

Representations of the real

York Way is now the unofficial border between the old and the new. For years a route north filled with warehouses, industrial units, and social housing, it sits uncomfortably in its new role. I turn right and head north. The contrast between the east and west sides of the road could not be starker. Social housing with over-flowing car park bins stares malevolently at the sparkling new structures over the road.

I stop at the northernmost border where the development meets the railway tracks that feed out of St Pancras station on their way to the Midlands, the Southeast and Europe. Here, construction is in full swing.

West and east sides of York way looking north

I cross York Way and walk into King’s Cross between Saxon and Rubicon court. These two blocks of affordable and social housing look out over a tangle of interconnecting railway lines leading out of King’s Cross and St Pancras Stations. A visual reminder to the occupiers of their economic position within the development.

Although there are no physical barriers to entering King’s Cross, the change in paving stone under my feet alerts me to the truth ‘that this seemingly unbounded public space is not boundaryless after all. The owner has all the legal prerogatives to exclude someone from the space circumscribed by these sometimes subtle and often invisible property boundaries’.[20]

Defining public space is generally based on what people believe they have a right to access with such places often being described according to their physical type – park, street, town square etc. They are an essential element of any city and are where people come together to ‘meet, talk, eat and drink, trade, debate or simply pass through (Mayor of London, 2009). As such, they are important nodes of social interaction which should be available for use (law permitting) on a completely unrestricted basis.

In 2011 The London Assembly Report Public Life in Private Hands remarked that ‘until the 1980s, any open space – whether it is green space, parks, open space, or streets – has generally been adopted by the local authorities, who experienced very little pressure for other uses’. With the expansion of Canary Wharf and other developments in the city in the 90’s came an expectation from developers that they would take ownership of any open spaces, with absolute control, to protect the value of their developments. This often included the enforcement of strict rules of use. Banerjee remarks that ‘The public is welcome as long as they are patrons of shops and restaurants, office workers, or clients of businesses located on the premises, but access to and use of the space is only a privilege and not a right.’[20] The very antithesis of ‘a right to the city’ as promoted by Lefebvre.

As I cross Lewis Cubitt Park I am struck by the pseudo-reality of the view and check to see whether what I am looking at is real or fake. This part of the development is still under construction and hoardings have been positioned to conceal the work behind. This creates a visual arena where real park and grass are lined with fake two-dimensional parklands disguising the workers toilets, offices and entry and exit points.

Hoardings showing parks and woodland line Lewis Cubitt Park and cover up building work

In the centre of the park is a sculpture titled My World and Your World by the artist Eva Rothschild and commissioned by the King’s Cross Central Ltd Partnership (KKCLP).[21]

‘My World and Your World’ by the artist Eva Rothschild

Writing about her sculpture Eva states:

‘We lie down beneath the tangle of steel branches and the city belongs to us.

The sculpture allows us to carve out this new space for ourselves.

We don’t just look; we are active within it.’

Eva Rothschild[22]

I wonder at her optimism in what appears to be such a sanitised space and doubt that this piece of the city truly belongs us. I think back with to the slightly ramshackle sculpture on Caledonian Road. Whoever made that were ‘active within it.’

I head towards Coal Drop Yard stopping to peer, photograph and take notes and have a slightly paranoid sense that eyes are on me. I feel more conscious of my behaviour than I did on the walk here where any activity out of the usual is generally ignored. Lyn Lofland claimed that it was ‘this living among strangers that creates the very basis of public space where civility towards diversity and difference rules.’[23]

What Simmel referred to as the ‘blasé’[24] the notion of loitering or wandering aimlessly alone with no apparent intent feels slightly naughty here and not how I am ‘meant’ to be spending my time. In his study of behaviour in public places, Erving Goffman speaks about how activities such as ‘reading newspapers and looking in shop windows’ are often employed by people in public as these are deemed to be ‘legitimate’ reasons to be somewhere.[25] Today it is the mobile phone that individuals stare at if they wish to become invisible in public.

As I go deeper into the development there are none of the broken paving stones, rubbish and scruffy kerbs found on the city streets I am more used to walking on.

A mosaic of images of the ground taken in the King’s Cross Development and surrounding streets. Can you guess which square belongs to which area?

Fake ‘graffiti’ - planned, anodyne and most importantly, easily removed

I watch as cleaning teams roam, as if on a constant horizontal treadmill - round and round - picking up every piece of litter, leaf, and dust that they find. A man with a pressure washer hoses down the pavements. Nothing is left behind. Tabula Rasa on a minute-by-minute basis. I think of my journey to the Overground this morning and noticing the chalk drawings on the pavement. Signs of both existence and the need for people to be creative.

Chalk drawings on the pavement as I walk to Homerton Overground

Who are Loki + Evie 04 and has their relationship survived as long as their tag?

Writing in wet cement, graffiti and chalk drawings are low-level acts of intervention between people and their built environment. They add both depth and richness to the space. It is a form of ownership and a message to the world saying:

‘I am here’

Alongside these man-made clues to the existence of humanity there are also visual clues to what is happening in the natural world.

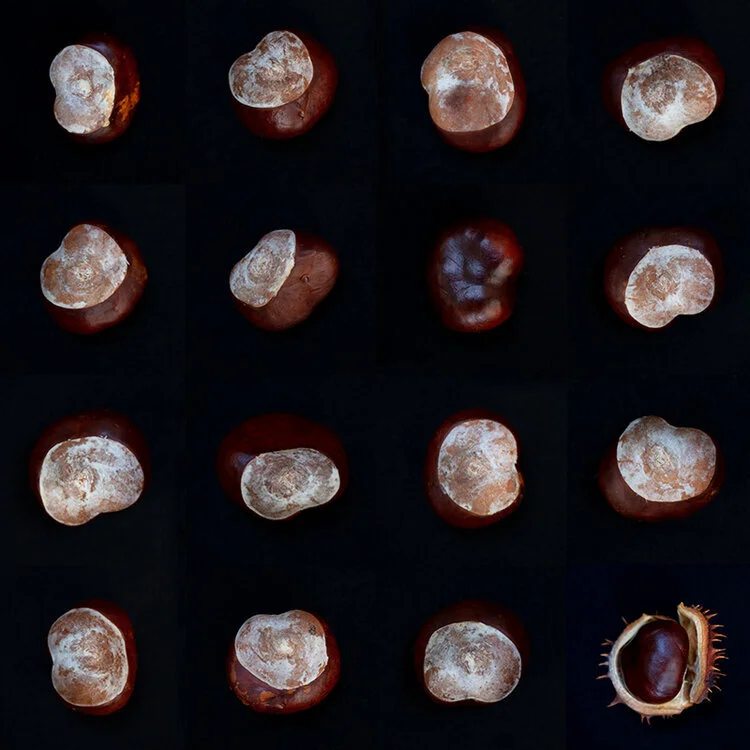

We know we are in autumn because, along with a change in the weather, conkers fall from the trees

These small and seemingly insignificant visual clues, when put together, build up manifold layers of images in my mind of people, places and objects across both space and time. They give me daily narratives that add depth and complexity to the world I move around in. In King’s Cross, these multiple layers of stories have no time to embed themselves. They are swept away before they have barely had time to settle.

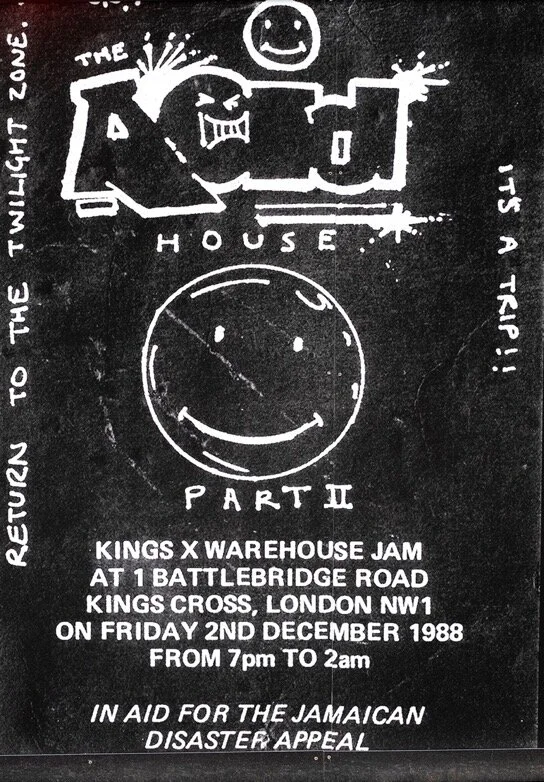

I arrive at Coal Drop Yard, the areas main shopping district. Built in the 1850’s to store the coal that came by train from Northern England, by the end of the 19th Century it had mainly fallen out of use and the building was taken over by Yorkshire firm Bagley’s who made glassware. I knew it well when it became part of the London rave scene in the 1990’s keeping the name Bagley’s.[26] I have hazy memories of walking down darkened, pot-holed lanes behind King’s Cross Station late at night, only to appear, as the sun came up, into a Victorian industrial wasteland. The area is now unrecognisable. Expensive shops fill each arch, glowing with exclusivity: Tom Dixon Designer, Joseph Cheaney & Sons Handmade Footwear, Blackhorse Lane Ateliers etc.

Nick Ferguson writes in The monuments of Kings Cross: A Visit to the New Ruins of London about witnessing construction workers removing and replacing the lime mortar and bricks in the Coal Drop Yard arches and that ‘little by little, the minute differences in mortar mix that has born witness to the evolution of the structures, to their periodic repairs over the passage of time, and which has thus made the past legible, are being irretrievably erased. At some point these buildings will all, both physically and visually, be bound together into a coherent and cohesive whole of what might be called ruin value.’[27]

Now a design emporium, this space once housed thousands of sweaty ravers

A quote by Paul Hirst comes to mind. ‘In attempting to remove grime and disorder from the urban environment, did modernist planners and architects also inadvertently wash away the spirit of the city?’[28] Spirit speaks to feeling, thinking, and behaving. To be spirited is to be enthusiastic, energetic, courageous.[29] None of which I feel as I walk through this ghost space.

Granary Square sits in the heart of the development. It has a large water feature, a seemingly mandatory fixture in all new developments. It is overlooked by Central St Martin’s School of Art and a slew of restaurants. As in the shopping district of Coal Drop Yard, there feels like very little purpose here. I watch as people hang-out in groups and pairs, hugging the obligatory coffee cup, and I think back to Caledonian Road and the purpose of that place. People going places to do things. Interacting with their built environment. King’s Cross on the other hand has seemingly become a tourist attraction. Michael Sorkin, writing about regeneration in New York described how ‘the new urbanity was consciously and programmatically preserving and recreating the bare minimum of urban form devoid of the formal and social mix that had once made cities lively and political; ‘there are no demonstrations in Disneyland.’[30]

In a place where so little appears to happen, I am amused by the constant material reminders of impending danger. To ward off litigation rather than as acts of kindness, I assume.

Metal sentries warn of potential hazards.

Comparing the many rich, diverse, and multi-layered histories I uncovered as I walked from the Overground Station to King’s Cross, the material world seems flat and one dimensional within King’s Cross. It has the feeling of a carefully crafted cover-up. Gone is the nuanced storytelling so readily available in the adjacent neighbourhood made, not by a marketing department, but by lives lived over centuries.

Here, history is researched, packaged, and laid out neatly in front of you. The Victorian buildings to past industrial endeavour now seem like conveniently positioned backdrops maintained primarily to assist with the commodification of the space. The only history I can find is emblazoned on the hoardings around the site. Carefully chosen to excite potential investors.

Hoardings recall a carefully chosen marketable segment of history that might entice the buyer

Coal Drop Yard with the Gasholders complex behind

The iconic grade II listed Victorian gasholders are now luxury apartments. After being refurbished, they were moved to a prime location within King’s Cross, perhaps to maximise land use/value. The gasholders remind me of 5* hotels. As you gaze up at the blank windows you are given no visual clue as to who resides behind these steel monoliths. No washing hanging up. No bikes or plants on balconies. All part of the leasehold agreement perhaps.

Ferguson writes that ‘having made it so far, rather than being pulled down to make way for the new, as is happening in so many other parts of the city, [the gasholders] are [....] in the process of being

incorporated into the development. They will be official ruins – part of a new story that the city will tell about itself.’[31] These monuments to decades of industrial toil and sweat have been carefully dissected, cleaned, reassembled and repackaged as beautiful backdrops for the purpose of global commodification.

The gas holders repurposed as luxury apartments. No clues to who lives there

With the decline of heavy industry and the abandonment of many of the former industrial buildings, by the 1980’s the area needed regeneration. Architectural historian Antoine Picon described this ‘anxious landscape’ as ‘composed of degraded and abandoned buildings, obsolete industrial leftovers and disjointed infrastructure, normally found on the fringes of the post-industrial city.’[32] By the 1980’s the area also had a reputation ‘as a socially blighted place, associated with street prostitution and drug-dealing.’[33] The coupling together of industrial abandonment and illicit street activity led to an increased effort to clean up King’s Cross that started in the 90’s and continued into the next decade.

Due to its historically cheap rent - by the 1980s King’s Cross was the lowest rent area for central London offices - and with a commercial building stock mostly unchanged since the 19th century, the area was ripe for redevelopment.[34] King’s Cross was by no means a wasteland though. The historical and social reasons that kept rents low enabled it to become a hub of creativity and diversity. Campkin describes the community as containing ‘a range of small-scale, socially oriented institutions including charities, trade unions and civil rights organisations.’[35]

In a film interview in 1992, the architect Norman Foster commented that ‘you can’t come across a site that is more ridden with all the problems of the inner city than King’s Cross. It’s a deprived area. It’s a wasteland, close to the heart of the city. All those sidings [and] Dereliction. An opportunity, an incredible opportunity.’[36]

A common trope when an area is deemed ripe for redevelopment is to firstly condemn the place as beyond economic and/or societal repair. In the late 1980’s London was ‘in the grip of a major property boom,’ an outcome of both neoliberal policies of de-regulation during the Thatcher period alongside severe underfunding of local authorities.[37] Lefebvre writes about how space itself is formed, lived and interpreted. He speaks about the ‘right to the city’ and that space is not inert or fixed, that it does not exist ‘in itself’ but is constantly changing, constantly being made and remade.[38] A group of activists and local residents called The King’s Cross Railway Lands Group formed to counter this perception of the area as being an ‘unproductive wasteland’ with an alternative and more positive dialogue that spoke to the space as being one of ‘radical politics, leisure and creativity.’[39]

I work my way across to the western boundary of King’s Cross along the Regent’s Canal and come up on Camley Street at the back of St Pancras Hospital where a spindly 1930’s water tower stands.

St Pancras Hospital water tower

The Victorian wall bordering Camley Street rises above my head on the western side hiding the gems that are the Dennis Geffen Annex, St Pancras Coroner’s Court and St Pancras Old Church and Churchyard, believed to predate the Norman Conquest and original burial ground of 18th Century feminist and writer Mary Wollstonecraft.

On the east side, Camley Street Natural Park (CSNP) sits low to the ground hugging the Regent’s Canal. A great example of Lefebvre’s ‘right to the city’ and the constantly changing nature of space. A former Coal Drop, it became abandoned in the 1960’s and was slowly reclaimed by nature. Residents,

appreciating its beauty, fought hard against its redevelopment and it was opened to the public in 1985, managed by London Wildlife Trust. The Trust describes it as ‘a very unique place [that] has been in the hearts and minds of many people for over 30 years. It has a charm that would be hard to replicate today without feeling contrived. It feels informal and cared for, the result of a place that has evolved through many years of dedicated development by a committed group of staff and volunteers.’[40]

Although the King’s Cross developers chose to ignore the ‘politics, leisure and creativity’ of the seedier parts of King’s Cross during their land acquisition, CSNP, saved by that very ‘politics and creativity,’ is now, ironically, positively promoted on the King’s Cross Website. Described as ‘a haven in the middle of one of the most densely populated parts of London [....] The park was created from an old Coal Yard in 1984.’[41] No mention of the local community activists and volunteers who saved the park from redevelopment all those years ago.

Camley Street Natural Park overlooked by the repositioned Gas Holders

There is an abundance of physical, material maps and signs within King’s Cross which seems at odds with a city so dependent on mobile phone apps to get about. Maps are used to explain and onceptuali abstract space. Blackman writes that ‘abstract space is planned and onceptualizeded with defined functions attributed to it by planning officials.’[42] Lefebvre’s third node of interconnected levels that make up the social production of space is ‘representations of space’ which are the onceptualized space of planners and architects etc., who use signs, plans and models.[43] Space is produced through social practices and material conditions meaning that ‘space and time are contingent upon and shaped by macro-scale policies and innovations, such as calendars and maps.’[44] Maps are a powerful way to ‘communicate meaning to the practices and experiences of navigation in everyday life.’[45] Looking at these maps, I realise that, rather than as a prevention to getting lost, they act as visual aids, directing you towards the centres of commodification.

A map directing people to a marketing suite

Arrows in Granary Square direct people to the shopping areas

However well secured, cleaned, planned, and mapped an area, inevitably life will attempt to assert itself into that bureaucracy. As I walk through Granary square, I encounter a small group of Hari Krishna chanting and shaking tambourines as they make their way through the space. A student from Central St Martin’s joins them, dancing wildly. It is an unexpected moment and I stop to watch. In less than five minutes they are moved out of King’s Cross by four policemen and a security guard.

Thinking about Lefebvre’s idea of ‘representational space,’[46] I wonder at the loss of people’s ability to effect local and global change in these proliferating privatised domains and what this means for democracy. Harvey, when writing about the uprising in Tahrir Square, Egypt in 2011 concludes that ‘What Tahrir Square showed to the world was an obvious truth: That it is bodies on the street and in squares, not the babble of sentiments on Twitter and Facebook, that really matter.’[47] Tahrir Square has also recently been modernised and securitised.

Hari Krishna being ejected from King’s Cross by Police and Security Guards

Campkin, in Remaking London, writes about a press conference held in a time leading up to the privatisation of British Rail where a large aerial photograph of the King’s Cross railway lands was encircled with a ‘thick red line - demarcating the territory to be flattened as if it were a piece of jigsaw, ready simply to be lifted out and replaced.’[48] The Maiden Lane/York Way map, on the wall of the canal as you are leaving King’s Cross, brings this to mind. It visually reminds the passer-by that there is nothing past this point, just emptiness.

A map as you exit King’s Cross warns you that there is nothing past this point

Continuing south along Camley Street I am soon walking between St Pancras and King’s Cross Stations. As I veer left into King’s Cross Station and Square, I mentally note how many police and security guards I have seen on my journey today. None on my walk from the Overground Station to King’s Cross. In a time when police are reportedly facing a ‘new era of austerity’ with some forces potentially facing their worst ever annual budget cuts fuelled by the coronavirus crisis, there seems no shortage in King’s Cross.[49]

Police and security guards are very visible within King’s Cross

King’s Cross Square at the front of the mainline station, is a grey, open space occupied by large stone benches. People mill about and sit on the benches, waiting for trains or waiting for people. A space of transience and impermanence where people pass through to elsewhere. Described by Marc Augé as ‘non-places’[50] these zones, found in airports and other travel terminals are generally spaces that ‘cannot be defined as relational, or historical or concerned with identity.’[51]

Around the perimeter of King’s Cross Station and Square there is a squat and immobile army of heavy steel bollards every 120cm’s. These Hostile Vehicle Mitigation (HVM) measures guard the space and ‘delimit where heightened security begins and ends.’[52] Beyond these bollards the real world of London continues at a different pace. This part of town that butts up to the security zone has a more ravaged, multi-layered, and lived-in feel that I am more familiar with. I see two homeless people a hundred metres apart. One is lying down asleep, no more than two metres beyond the HVM bollards, while the other is outside McDonald’s. Within sight of the police and security guards patrolling King’s Cross, they are ignored. Davis wrote in 1992 that Los Angeles was ‘inexorably [....] mov[ing] to extinguish its last real public spaces, with all of their democratic intoxications, risks, and undeodorized odours.’[53] A warning from nearly three decades ago that resonates today in London.

Life outside the securitised zone

I make my way back up York Way, take one more turn around Granary Square and return home along the Regent’s Canal, passing the Hari Krishna band. I leave the canal at Caledonian road, glad to be back among the layers of stories and events that for me defines lives lived.

Conclusion

My strong personal attachment and knowledge of this part of North London, combined with a methodology involving walking and visually recording has given me an embodied, street-level view of the realities of hyper-gentrification on both people and place in King’s Cross and the surrounding area.

King’s Cross is a passive, anodyne, and overly curated environment to spend time in. The constant presence of security guards and rotating cleaning teams do, on the surface, make the place seem secure and cared for, but for who and at what expense? The apparent lack of any form of diversity acts as a barrier to inclusivity and the capacity for people to have real and creative encounters and experiences. Caledonian Ward seems, on the surface to be disconnected from King’s Cross with the two states existing back-to-back.

Henri Lefebvre did not live to witness the impact of hyper-gentrification and planetary globalisation of cities has on the production of space and I wonder if his idea that ‘space was not inert or fixed, that it did not exist ‘in itself’ but was constantly changing, constantly being made and remade’ would ring hollow in today’s globally regenerated zones.[54] I get no sense of the notion of ‘made and remade’ in King’s Cross that I saw repeatedly on my short journey to the site. These produced, commodification zones have an unbending rigidity where the chance events or encounters are not only unlikely but are actively avoided.

Memories are the result of lived experiences situated in abstract space. The result of King’s Cross being remade as new, every hour of every day, means that there is little time for the build-up of those visual layers of history that speak to the multitude of stories and lived experiences that enrich and give depth to a place. Individual and group histories I witnessed all around me as I walked along Caledonian Road and Copenhagen Street.

Augé considered places of transit to be non-places. That term envelops the entirety of King’s Cross beyond just the station terminus. The securitisation, sanitisation and commodification that goes with hyper-gentrification results in disconnected spaces suffering from a lack of ‘there-ness.’ The equivalent to arriving at your destination without ever having taken the journey.

Map of walk from Caledonian Road and Barnsbury Overground Station to King’s Cross

For an interactive map of my walk please click the link below:

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/1/edit?mid=1oPUPPClwlN4_cuuyxeyR5vrgRsEm2tYg&usp=sharing

All photographs copyright of Rosie Hallam

Notes

1 Crown Copyright https://www.gov.uk/government/news/kings-cross-completion-shows-us-britain-knows-how-to-deliver-says-infrastructure-minister.

2 (2000: 105 De Certeau, M. 2000. Walking in the City Pp. 122-145 in On Signs, edited by Marshall Blonsky. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.)

3 ([1908] 1997 Simmel, G. ‘Sociology of Space. Pp. 137-170 in Simmel on Culture, edited by David Frisby and Mike Featherstone. London: Sage),

4 Shepard, N. (2011) The Living Mountain. Edinburgh: Canongate Books Ltd.

5 Crystal Roof (2021)(a) Demographics of Caledonian Road, London, N1 1DT. Available at: https://crystalroof.co.uk/report/postcode/N11DT/demographics?tab=ethnic-makeup (Accessed on 15.12.2020).

6 Word4Weapons, (2020) Available at: https://www.word4weapons.co.uk

7 Ghost Bikes. (n.d) Ghost Bikes. Available at: http://ghostbikes.org

8 Morris, J. (2016) Islington Gazette: Family of tragic Alan Cartwright celebrate teenager’s life one year on from murder in Caledonian Road. Available at: https://www.islingtongazette.co.uk/news/family-of-tragic-alan-cartwright-celebrate-teenager-s-life-one-3748834

9 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.39.

10 Thornbury, W (1834) Climbing the Caledonian Park Clock Tower. A London Inheritance (2015). Available at: https://alondoninheritance.com/tag/caledonian-park/

11 Bangs, D. (2018) Dave Bangs Available at: https://www.forwallswithtongues.org.uk/artists/david-bangs/

12 London Mural Preservation Society. (2021) Tolpuddle Martyr’s Mural. Available at: http://www.londonmuralpreservationsociety.com/murals/tolpuddle-martyrs-mural/

13 Martin, J. (2008) Lisa Pontecorvo. The Guardian Newspaper. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2008/oct/17/

14 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.38

15 Stevens, A. (2010) The Future of Landscape. 3: AM Magazine. Available at:

https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/the-future-of-landscape-doreen-massey/

16 Blackman, K. (2019) Securitizing public space: A study of King’s Cross Station & Square. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies. King’s College London.

17 Massey, D. (2013) Doreen Massey on Space. Social Science Bites. Available at:

https://www.socialsciencespace.com/2013/02/podcastdoreen-massey-on-space/

18 Massey, D. (2005) For space, London: Sage.p.9).

19 Massey, D. (2013) Doreen Massey on Space. Social Science Bites. Available at:

https://www.socialsciencespace.com/2013/02/podcastdoreen-massey-on-space/ (accessed 13.12.20).

20 Banerjee, T, (2001) The Future of Public Space: Beyond Invented Streets and Reinvented Places. Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(1), pp.9–24. P.12

21/22 King’s Cross, (2021 b) My World and Your World. Available at: https://www.kingscross.co.uk/my-world-and-your-world

23 Lofland, 1973 in Bodnar, 2015. p.2091. Bodnar, J. (2015) Reclaiming Public Space. Urban studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 52(12), pp.2090–2104.

24 Simmel, 1971, in Bodnar, 2015. p.2091. Bodnar, J. (2015) Reclaiming Public Space. Urban studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 52(12), pp.2090–2104.

25 Goffman, E. (1963) Behaviour in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. New York: The Free Press. p.59.

26 Whitehead, A. (2018) Curious King’s Cross: Raving at Bagleys. Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications. Extract available at: https://www.curiouslondon.net/extract-raving-at-bagleys.html#

27 Ferguson, N. (2017) The monuments of Kings Cross: A Visit to the New Ruins of London. Journal of cultural geography, 34(1), pp.93–114. p106-107

28 Campkin, B. (2013) Remaking London, Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture. London: Bloomsbury. p.1.

29 Walter, E. (2021) Cambridge Online Dictionary. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/spirit

30 Sorkin, M, (1992) (ed.) Variations on a theme park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. New York: Hill and Wang. p.xv).

31 Ferguson, N. (2017) The monuments of Kings Cross: A Visit to the New Ruins of London. Journal of cultural geography, 34(1), pp.93–114. p.106.

32 Picon, A & Bates, K. (2000) Anxious Landscapes: From the Ruin to Rust. Grey Room, (1), pp.65–83. p.65

33 Campkin, B. (2013) Remaking London, Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture. London: Bloomsbury. p.108.

34 Edwards, M. (2009) 'King’s Cross: renaissance for whom?’ Chapter 11. In ed. Punter, J. Urban Design, Urban Renaissance and British Cities, London: Routledge. p.1.

35 Campkin, B. (2013) Remaking London, Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture. London: Bloomsbury. p.111

36 Crockford, S. (1992) (dir.) Kings Cross: David and Goliath. [Documentary film].

37 Edwards, M. (2009) 'King’s Cross: renaissance for whom?’ Chapter 11. In ed. Punter, J. Urban Design, Urban Renaissance and British Cities, London: Routledge. p.1

38 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.90.

39 35 Campkin, B. (2013) Remaking London, Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture. London: Bloomsbury. p.111

40 Friends of Regent’s Canal. (2017) Camley Street Natural Park, Design & Access Statement including Conservation Statement. Available at: http://friendsofregentscanal.org/features/property-devt/Kings-Cross/Camley-St-visitor-centre/docs/Design%20and%20access%20statement%20_1of10.PDF. p.4.

41 King’s Cross. (2021) Camley Street Natural Park. Available at: https://www.kingscross.co.uk/camley-street-natural-park

42 Blackman, K. (2019) Securitizing public space: A study of King’s Cross Station & Square. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies. King’s College London. p.8.

43 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.39.

44 Gieseking et al. (2014) Section 9: The Social Production of Space and Time. The People, Place, and Space Reader. Available at: https://peopleplacespace.org/toc/section-9/

45 Duggan, M. (2018) Navigational Mapping Practices: Contexts, Politics, Data. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 13(2), pp.31–45. DOI: Available at: https://www.westminsterpapers.org/articles/10.16997/wpcc.288/ p.1.

46 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.39.

47 Harvey, D. & American Council of Learned Societies, (2013) Rebel cities from the right to the city to the urban revolution Paperback., London: Verso. p.162.

48 Campkin, B. (2013) Remaking London, Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture. London: Bloomsbury. p.110.

49 Dodd, V. (2020) Police in England and Wales facing 'new era of austerity.' Available at:

50 Augé, M. (1994) Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London. Verso.

p.79

51 Augé, M. (1994) Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London. Verso. p.103.

52 Blackman, K. (2019) Securitizing public space: A study of King’s Cross Station & Square. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies. King’s College London. p.13.

53 Davis, M. (1992) Fortress Los Angeles: The Militarization of Urban Space. In Sorkin M (ed.) Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 154–180. p.180.

54 Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. p.90.