Fred Adam

Fred is a New Media explorer, co-founder of the CGeomap project and founder of the Lab GPS Museum. He is also a researcher and Freelance Art Director in spatial narratives in the outdoors. Fred is especially interested in the interactions between the world and smartphones, in time and space, from the very small to the very large and from the past to the future. He has a special interest in investigating how mobile technology can help us to understand better and preserve the Earth by involving people into transformative outdoors experiences. With the curator and artist Geert Vermeire, he launched the Locative Media Supercluster web portal in 2020, which is a space for organizing collective mapping events and online courses. Previously, he has been inspired by and collaborated with David Merleau Andy Deck, Celia Gradin, Robert Filliou, Rich Blundell, David Abram, Verónica Perales, Dan Mc Veigh, Stephan Harding, Francisco López, Chari Cámara, José Ramón Alcalá, Rebecca Solnit, Brian Swimme, Sylvie Marchand and Keiko Tanaka.

Mike: How did you get into located media? Could you explain your trajectory into locative media artworks?

I did fine arts in 1991 during which we were witnessing a transition between analogue and digital artwork. Soon, I started participating in the digital lab at the University of Nantes in France. We started, as a small group of people, to experiment with interactive nonlinear stories with the use of a software called ‘Macromedia director’. Also, I travelled to Spain in 1993, and had a very transformative experience spending one year in a small village with my computer. There, I started to write a travel book about my interaction with people in the village. It was ‘locative’ in the sense that I was in a village with my computer and talking to people, using recorded media and creating a story about those interactions in that place. After this, I worked in Cuenca (Spain) at the Museo Internacional de Electrografía, which specialized in artworks made with printers, machine, photocopiers, copy machines, etc. It was a time of transition; a lot of people were starting to use machines to create artworks and I spent several years there doing a lot of projects.

It was 1997-98 that the internet started; it was a big change because we went from a local creation to the global context of audio-visual interactive creations. This was a significant change and I felt lost in this immensity, this ocean. It was quite scary to tell you the truth. Questions emerged: What is the relationship between artworks we could do at the local level, and what kind of work could we do at the global level. During that time, I had a chance to meet people like Verónica Perales (Spanish artist) and Andy Deck (American artist), who are both from the generation of ‘net artists’ and some of the pioneers. We created a collective called Transnational Temps and explored this problem, this relation between the appearance of new digital places and artworks, and the disappearance of biodiversity on Earth.

We focused on this question at the global level. Historically, around 2000-2001, locative media technology emerged, and in 2007, the first iPhone. It was really exciting to go back to the ‘local’ through technology by placing one foot in the local and the other foot in the global, which is, I believe the best context for digital interactive creations.

Mike: Net Art was a fairly niche corner of the arts community in the early 2000s. Did you consider yourselves ‘Net Artists’?

Net Art was centered on questioning the code more than anything. It was not about questions of the environment, and biodiversity and other kinds of stuff. We (Transnational Temps) were encouraged to be this way, it was like a bubble, where we imagined a new market made of digital-only creations (see net artists like Jodi, for example). However, it was a very narrow vision and we were not interested in Net Art and so we never entered the market. We were borderline, more interested in questions relative to the local and the global, to create a local connection with the internet.

Mike: We've talked about the three waves of locative media art before, as a way to think through the different phases of this work, from early Net Art through to the explosion of locative media projects after the iPhone came out in 2007. How do you differentiate between these waves?

I used to think in terms of the technology. CD ROMs, the internet and then locative media. However, it seems that now everything is blurred. What matters is not if it's digital, but what the message is? What is the impact? What is the ability to connect with people through the artwork? So, yes, these boundaries, these boxes, are dissolved today. I don't think they exist anymore.

Mike: In terms of your journey through this, and the communities that you joined, would you say that there was any defining point where you joined the ‘locative media community’? And how do you see yourself and your role within the locative media arts community?

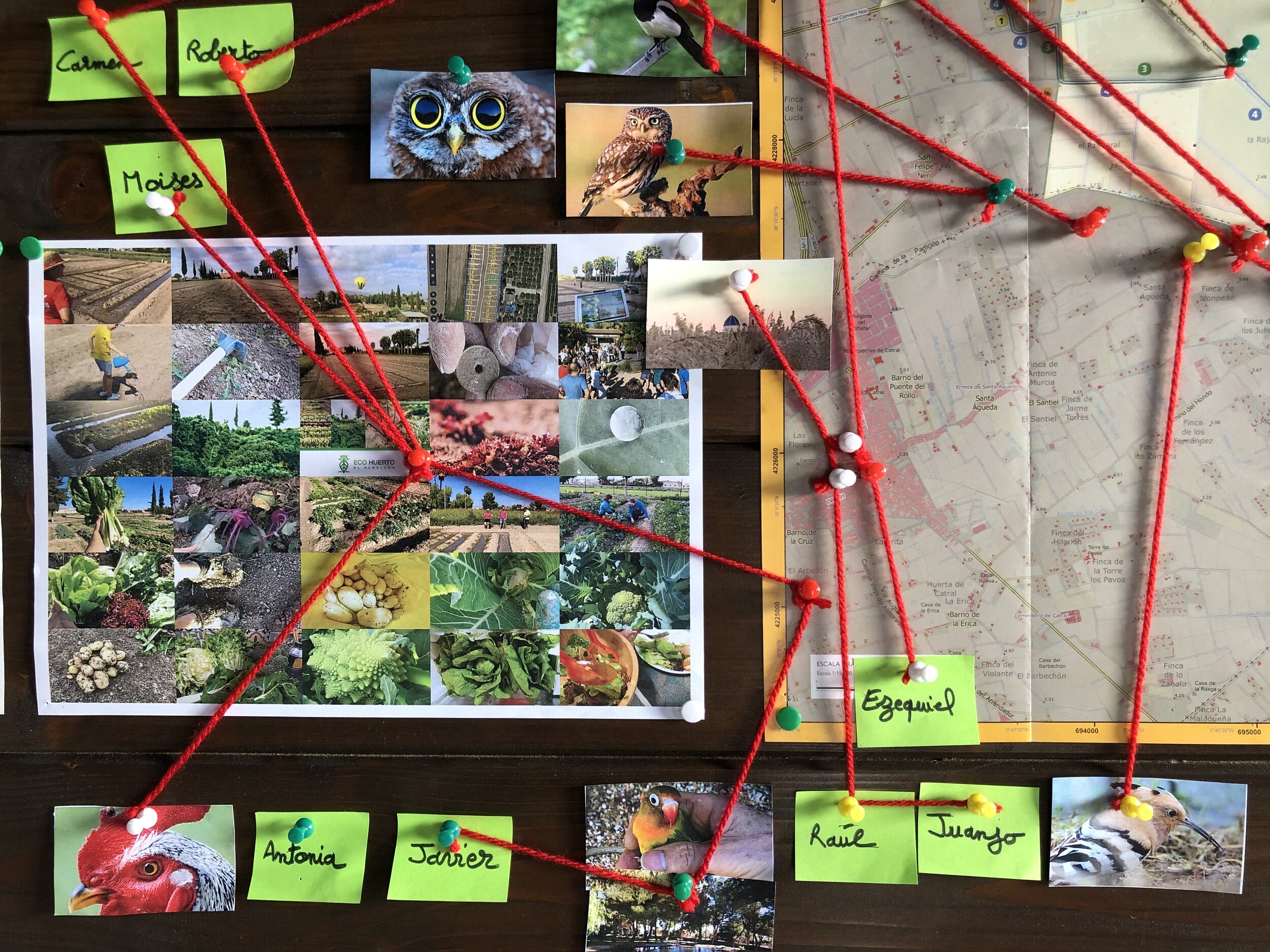

Locative media has really been a community network from the start because it was not yet in the mainstream. There was no market for it. It was an experiment by programmers and artists. From the start it was a big community, but the last two or three years have seen even bigger changes. The artworks we created early on were for the audience. You created a locative work with your friends, afterwards you make your workshop, create interesting ideas and deliver it as a single experience. Now, however, the work is maturing and we understand that it's not only about delivering a product or an experience for one person. It's about generating communities around understanding territory, place, time, the global and the local in a better way. For example, the most important part of CGeomap, the platform we created in 2016, is the process of community creation around these issues.

Mike: So it's more about the process of developing a particular app, and then a community based around that app or that website?

Yeah, that's my feeling. At first the technology is very hypnotic, and you are very excited, but you forget to see the big picture. When we look at it with a certain level of maturity and distance the collaborative process is what matters. We have intuitions as creators and artists, and sometimes we know, but we need time, years, to realise this potential. I understood from the start that locative media was a good way to articulate technology in ways that I wanted. I knew it from the beginning, but now I understand it better by going beyond just creating media or resources.

For example, we did a project with the Escoitar group and the Cultural Centre of Mexico in 2014-15 with Horacio González. We made a map of the Spanish exile from 1936-1939, regarding the civil war in Spain, where 25,000 people fled by boats to Mexico. They were welcomed by President Lazaro Cardenas in Mexico to escape from Franco- the dictator. It is an exciting example of a positive integration of exiled people into Mexican society and culture. We interviewed ancestors from these people, as well as historians and people interested in the topic, and ran workshops and led some walks. There was also the participation of young people, which resulted in an exciting cultural exchange, something that does not happen often today. It was a success, although it was a very dramatic subject because it deals with a situation of people who suffered so much and had to leave their country. It’s important to say that it's not a problem to talk about Civil War in Mexico, but it's a very big problem to talk about the Civil War in Spain, where it remains a taboo. The project was a very transformative experience.

What is very good with locative media and storytelling is that it is not like cinema, documentary or painting. Everything can be a reference for you. Cinema can be referenced, a documentary can be a reference, the game industry can be a reference, literature and poetry can be a reference, sound creation can be a reference, so it is a very exciting position where everything is possible. Locative Media is like a crossing of languages.

Mike: It’s very interesting to hear about how locative media can be used to engage young people, and how you use walking as a method for engagement. Was this always a priority of yours or was this something that just came out of the work?

Locative media as a terminology is wrong. It is not complete. Instead we should say ‘locative-time-media’ because when you walk, you explore a place in time. Locative media has this ability to work across the dimensions of place, through time and space. Through it, we can start to think about the geological layers of the place as well as reintegrating the ancestral values of place. When we spend time in place, especially in nature, we understand the transmission of values through generations, which is something I believe we have lost, because there is an artificial barrier between generations. It's hard for young people to talk or to accept information from older people. Older people feel disconnected from society; therefore, they disconnect themselves from society. This is a drama because we need to keep the flow of experience and knowledge. So, a natural way to apply this understanding of time and space is to involve young people, as we did with elders in Mexico. It's important to keep the legacy of places, in that location, because what happens with all these materials, these memories in 50, 100, or 200 years if we do not? That's a big, big problem, and really leads us to a conversation about digital conservation and the digitalization of memories in place.

In regard to walking, the act of walking it's indivisible from the act of thinking, and we think better when we walk. The body is the starting point of any experience because, of course, there is no separation. Locative media and walking have value because together they make this connection with our mind and body. To walk is to tick in time, in the sense that you have a certain speed, and when you walk it is like a clock, one step after another, moving in space and time. There is a marvelous opportunity here [for locative media] to build a story or build a locative experience relative to the distance you cover and to your speed. We might look to the language of cinema here, to learn how to deliver and deal with a new dimension, which is all about the body and the spirit.

The best example I could give you is a project we did with Stephan Harding at Schumacher College in England called the Deep Time Walk, where we played with our bodies and our perception of space and time to tell stories. By converting a step into a timescale, we converted one step to equate to 1 million years, so that when you walked 4.6 kilometers it would be the equivalent of walking along with the evolution of life on Earth.

As you walk the 4.6 kilometers using the app, this scientist is telling you the story of the evolution of the Earth, of life on Earth. There’s also a Shakespearian fool character, asking strange questions to the scientist. So you have this App that dictates your walk through space and time, which is marvelous. There is an embodied cognition going on, by converting the motion of the body into time-space or space-time. The work gives you a sense of scale you cannot understand only in your mind, you have to understand it through embodied cognition. We, as humans, don't have a sense of time. We believe that we are around since the start and that we are cleverer than any tree, any bird, or anything around us. We arrived just 300,000 years ago, which is very few, and that’s what bodyily perception gives you. So, as you begin to walk the 4.6 kilometers, you realize, where are the humans? You have to wait for the last five steps to see that.

Mike: I love the idea that it's about working with several different axes, both temporal and spatial. There is also this idea of scale which is important to how we understand both what we're doing and how that connects to deep time.

You should try it. There is an app to share and you can autoplay at home if you want. I'm so happy to have done this project, but there is no market for this type of thing, which is a bit of a problem. We are doing interesting things with locative media, but because there is no market, no mainstream, the project has a very short life; it's expensive to do this programming, and to update the technology all the time.

Mike: That's a good point about the finances of projects like these. As you say, it is expensive to run the project, but then even more to maintain them, to conserve them.

Yes it is, but really, the conservation of the media is absolutely impossible. Let's be honest, it's not possible, unless you have a lot of money. It could be possible, but not yet. Also, the market is not interested in it because it's good business to have no permanent access to these memories.

What matters more is how you tell the story and who you share the story with. What kind of message do you want to communicate with the story? That's the real spirit of locative media. What is necessary is for us to keep the stability of creative worldviews inspired by the ancient times, inspired by the understanding of space and time, inspired by a sense of community and exchange, inspired by gratitude, to our lives, to our years.

Mike: I want to change tack slightly to talk more about your work with CGeomap and with the GPS museum. Why did you initially start these projects?

We originally created CGeomap for a workshop on locative media. We wanted to control and have our own tools. It came from our desire to create open-source tools for the community, but it was extremely difficult to create CGeomap because we were not a company. People come and go, and it's also technologically complicated because we don't do apps. We emulate apps on web browsers and mobile phones.

With CGeomap we introduced the possibility of creative collaboration of locative content – making things together - which is new. I don't know anyone who is doing that right now. It's simple in terms of the possibilities you have, but it gets us to a place where collaboration is central to what we want to do.

Today we are still working on improving the tool and I am expecting to arrive at a certain moment soon, where we stop and keep it as it is, just adding small updates. I believe that we have almost arrived at this point. We don't want to make it more complicated. We have a new programmer now, working on Cité des sciences in la Villette in Paris. He is a Jedi of programming, and thanks to him we are getting there. But it is difficult, you know, because the technology is always changing; how HTML works is changing, navigators are changing, the operating system is changing. It's very, very difficult, but we continue to work on it. It takes a lot of energy and time, but we have a reason for doing it.

Mike: Following on from this, I'd like to know how you began working with Geert and how that collaboration started because we, me and Cristina, met him at the same time, in September 2019, but we’ve only known you through Zoom, which is a strange situation, but it works. I always want to know how you and Geert got to know each other and how that partnership works?

I have such good communication and collaboration with him. I have the feeling that I have known him for a long, long time, which is not true. We didn’t even meet each other until recently. Even then we just met one time, for a few hours, when he came to visit me in the wooden hut in Spain. We just built our relationship online, you know. There is really good magic and alchemy between us because really we have two parts, two pieces that fit very well together. This is a beautiful story. Recently, we created the Supercluster.eu site together as a meeting ground to teach collaborative media. It was a chance to discover and collaborate with amazing artists like Stephanie Whitelaw, Fay Stevens and Elspeth Billie Penfold and others.

Mike: Working with you both, it is like you have known each other for years!

Yeah, it's true. We found ourselves, over the years, becoming part of a universal family of people working in the same direction, having the same targets, or visions, and at the end, we finally got to meet each other. It reminds me of the French artist, Robert Filliou who talked about the eternal network... Before the internet, a long time before the internet, was this sense that we [artists] were creating a network, an invisible network of people doing similar things. Geert and I got tied up in this network together.

Mike: Finally, have you thought about this in terms of locative media and how you see it developing in the future?

Yes. We talked about the potential third wave of locative media and I am very, very concerned, about the disappearance of digital information. There are absolutely no guarantees that all the work, all this time people are spending on it, all the memories of places will be preserved. This is my first target for 2021, to continue to have the conversation with interesting people like Hamish Sewell in Australia, who are working on the idea of universal locative media formats, which is so important. So yes, I would love to be able to offer a way of conserving locative media work in the long- term. If we do not preserve these media and content, people will only be able to access mainstream media and content in the future, which is very problematic. I do not know if there is a solution, but let us try… let us try.