Dreaming of a Post-Covid World: Drawing Maps, Imagined Places and Pandemic Storytelling

Kimbal Quist Bumstead and Sol Perez-Martinez

The global spread of the Covid-19 pandemic at the beginning of 2020 brought radical changes to the lifestyle of millions of people including abrupt restrictions to our freedom to roam.[1] The strict limitations to the places we could inhabit and visit gave way to the yearning for the places where we wanted to be. Limited for months to a single space, our imaginations worked as a liberating tool to visit places out of reach. Soon it became natural not only to imagine those places from memory but to create in our minds new alternative worlds, ideal places, utopias.

In March 2020, the world changed as social distancing measures and stay-at-home rules were implemented in multiple countries around the globe as a response to the pandemic. Personal geographies shrank to the spaces within the walls of a home, the route taken to the local supermarket, or the distance that could be travelled on foot or bicycle within the space of an allotted exercise hour.[2] Many people discovered their local environments in ways that they had not done before. They made friends with their neighbours, ran marathons on balconies and kitchen tables became offices and schools. The domestic space became a gateway to the world beyond, not only via screens and the internet, but also through our imagination and our capacity to dream. Quarantine highlighted spatial and social inequalities exposing socio-political realities, but also created a space to imagine social change, prompting questions about alternative futures.

Dreaming of a Post-Covid World is a curatorial project that sought to explore the practice of map making as a form of visual storytelling within the context of the global pandemic. Via an open call, people were invited to send handmade maps of their quarantine experiences and their dreams for the future. We invited people to map or draw their ideal place, a place they dreamed they could visit in a post-covid world, a place they wished to live in, or perhaps a local place they wanted to transform. The task could be interpreted as abstractly or concretely as they wished, it could be mundane or absurd, real or utopian, simple or complex. We aimed to curate a selection of different responses to a purposefully broad theme prompted by three questions:

* How do you imagine an ideal post-covid world?

* What would you like to encounter in your city or your neighbourhood post-lockdown?

* Can you visualise a place from your dreams?

Open call

Contributors to Dreaming of a Post-Covid World were invited to map their experiences of the global pandemic, real or imagined. There were no specific guidelines to suggest what a map is, nor what it should look like. Also, there were no limitations in terms of format or medium as long as the submission was an image that could be later published. For consistency we opted out of video and sound installations. Each author submitted an image, a title, the place of confinement where the image was produced and a paragraph explaining their contribution. We present here a selection of sixteen submissions including drawing, collage, photography and mixed media from five countries, in three different continents.

Andrew Howe

Andrew Howe, Frankwell Quay Utopia, Shrewsbury, UK, collage, 2020

My utopian map evolved out of walks in my local community of Frankwell in Shrewsbury. It is a collaged grid of prints, photos, and rubbings from the landscape that I gathered when mapping the walks. I created a utopian combination of cultural and sustainable uses building on what already exists, as a personal response to ongoing community consultations across Shrewsbury. These discussions are intended by the local council to inform development of future plans for the town. It seemed to me that with relatively little investment in new infrastructure and a more radical change in attitude to sustainability, the historic riverside area situated between the relatively recently built University and Theatre could be a vibrant, cultural centre. I would like to think the map reflects what I hear from many people about their hopes for a green recovery, and my hope is that this map could be used to provoke public debate with the community about how they might be actively involved in shaping the place we live in.

Clare Qualmann

Clare Qualmann, Tentacular imaginary, London, drawing, 2020

I was thinking about the way that lockdown required a return to the super-local and to a greater extreme an introspection into bodily worlds. Thinking about the folds and crevices of the inside of my body – the interfaces with external matter – food, drink, bacteria, viruses, air, water, pollution etc. But also thinking about sending tentacles’ out into the world, longing for touch, wanting to extend and interact/intersect with others. So, it’s an imaginary way of sending out new feelers.

Crab Man

Crab Man, Archipelago Island, Plymouth, UK, drawing, 2020

Sketch interrupted. The space on the rocks. Watching my friend swim in the Sound. Usually I swim too, but I want to sit in the sun and draw. Lockdown is easing and my lonely rock is soon crowded and I leave. The dream is not after Covid, but in the closest relation to Covid without getting it; the dream is attending to Covid, giving attention to it. To its blue plane-less skies, it's turning up the volume control on the birds, the return of the air; for a while there was brief dreaming; folks sat in their front yards wondering why they had been rushing so much. In the quiet streets the houses stood forward as personalities. We strolled up the middle of formerly noisy racing roads; joined in the applause in unfamiliar streets. After dusk the streets glowed fragile, like early Dr Who sets. Something new could materialise, was materialising. Somewhere at the edge of this new calm, there were tubes, panic, coughing, dying out of time. Inside the bubble’s brief week, there was something that threatened to suck a whole system down; and then royals and celebs and Tories joined in the applause and solidarity was commodified. When Lockdown eased the volume, control was given back to the machines, the blue sky smeared with contrails once more, the air tinted. The possibility retired to the island, strung in threads of difference to others, the dream isolated and inaccessible for now, and I was forced by the proximity of others to pack away my sketchbook, sharpener and pencils and walk up the granite and concrete steps back to the wall and wait for my friend.

Di Parodi family

Di Parodi family, Family Concert, Santiago, Chile, drawing, 2020

2020 has been a great challenge for all of us. In different ways, each of us felt a lack of control in a number of new situations happening around us that nonetheless affected us directly. Lack of freedom, new realities, work crisis, educational problems, confinement times, lack of products, the passing of friends and family members, among many other things which have a negative connotation. Being the parent of two children, aged four and seven, part of the challenge was to create a lockdown routine that kept them away from screens. We wanted to interact and educate our children while at the same time enjoy their childhood and give them the security that everything would be fine.

This series of family drawings represent the collective task of building an imaginary world where everything is possible and permitted, where each family member is well received to intervene, in their own space and sometimes in the space of others, respectfully sharing for the development of a common objective which is colourful and familiar. These drawings represent a future which is respectful and kind, built from within a family.[3]

Emma Fält

Emma Fält, Maps of softness, fluidity and energy, Finland, print, 2020

I used suminagashi – a printing technique to create a series of small-scale drawings that are created with water, Indian ink and finished by adding neon orange ink. When I started the process, I was thinking a lot about fear and the place it's coming from. I found that place inside and it was connected to human need to control the situation. The technique I am personally interested in is done with materials that are reasonably difficult to control: ink on the water surface and very delicate paper that needs to be lifted from the water when not dry. My map talks about the need to go back to fluidity and softness that is created by waiting patiently and noticing as well as nourishing oneself with something that comes from the near environment. My hometown used to be an island and where I live and work, I am surrounded by the lake. The process of making let me be present with what I have now at home and enter a process that is something very delicate and fragile like life itself. I decided to be the subject and actively change the map by adding new traces after the more surprising and uncontrolled elements were printed. By adding the neon colour, I was searching for some new energy from myself to live with the situation. I navigated on the map and followed my own needs. By creating these energetic flows, I conquered my fear of not knowing what is going to happen.

I hope in the post-Covid world we could become more aware of our need to control what can’t be controlled. For that to happen I believe we need a lot more softness and fluidity in our everyday life.

Joel Seath

Joel Seath, Rishen, UK, drawing, 2020

During the UK’s early summer lockdown of 2020, a cohort of two classes of Year 5 children (nine- to ten-year-olds) were remotely communicated with via Google Classroom. They were prompted to offer imaginative post-Covid mappings on a voluntary basis. Analysis of the children’s submissions relied predominantly on their own annotation notes, the staccato traces of their written or verbal follow-on stories, and on what is explicitly referenced, as drawn, in the children’s art. Inevitably, some adult interpretation also ensued, but awareness of children’s right to expression was key in keeping this to a minimum: this was a project about their thoughts and feelings, after all. Some common themes were evident: forms of escape; the importance of play, nature, family and friends; the missing of day-to-day places that we otherwise took for granted. The children’s submissions, collectively, were replete with connection.

Kimbal Bumstead

Kimbal Bumstead, Arakicho, London, UK, collage, 2020

During the lockdown, I dreamed of many places that I wished I could go, places that were out of reach in both space and time. One of those places that kept popping up in my thoughts was the place my partner and I lived whilst we spent three months in Tokyo some years ago. It is not a place I know intimately, but three months was long enough to explore all the neighbouring streets, their quirks and curiosities. I collected some paper materials that reminded me of Tokyo, brightly coloured pages of magazines and some cutout sections of my own abstract paintings that were inspired by my time there. I started by drawing a sketch of the room that we lived in, imagining myself there. I then branched out into the shared kitchen down the stairs and out of the building onto the street. As I stuck down pieces of paper, I traced an imaginary journey through the Arakicho neighbourhood, as if I could see myself walking through the streets.

Laurien Versteegh

Laurien Versteegh, I walk the line, Driebergen, Netherlands, collage, 2020

The starting point was that during the corona lockdown my family and I walked in the garden so much, a path appeared. The grass just disappeared completely. So, for me that is my map: a self-made path. I thought if this lockdown goes on too long the path will go into the ground and I will disappear. I imagined how nice it would be if there was an escalator under the ground, beneath my self-made path to take me somewhere exciting: out of the bloody garden!

Linda Knight

Linda Knight, Mapping Privilege, Melbourne, Australia, drawing, 2020

The image is part of a series of inefficient mappings of posthuman, Anthropocene citizens in a time of catastrophic disruption. Posthuman citizens are transversal: composite, permeated by chemicals, micro-organisms and viruses that invade bodily boundaries. The series maps the shadows and movement of these posthuman citizens to give presence and substance to all manner of matter and bodies and to visualise a cosmopolitical civics of urban life. The maps gesturally mark affective and relational imprints of colonisation and privilege and address how understandings of civics and citizenship must shift in these times of great change.

Margaret Ramsay

Margaret Ramsay, Shimanonimbus, Faversham, Kent, UK, Mixed media, 2020

Before lockdown I travelled regularly by train from Faversham in Kent to London to visit galleries and for art courses and made artworks based on my journeys, my Space Out of Time’. These included an installation of stitched overlapping booklets of tracings of maps along the route. I primarily work with multi-layered, worn, textiles: double-sided semi-translucent loops, referencing the continual repeats of my travels and linear records of walks on painted strips of calico.

In lockdown, my focus has been very local, using my bike to explore the countryside around me. I’m increasingly risk averse and feel safer on my bike than on foot, a travelling island with limited contact with people. My map, Shimanonimbus,’ uses photos of my bike, altered in Photoshop, de-constructed and collaged onto a background of painted newspaper with glimpses of underlying text and colour. The shapes remind me of places visited and where I hope to travel to once more.

Menekse Aydin

Menekse Aydin, Map of Eatable Lands, Turkey, mixed media, 2020

This map does not last. It is not an archive for now or future. On the contrary, its presence is ephemeral and as such it cannot erase the presence of the people and stories it represents. This map is not to be looked at from a distance, but it is to be broken into crumbs, eaten with satisfaction, incorporated in the body of strangers or any visitors of the area. It participates in the transmutation that governs life. Like most of my objects...

Michael Farrie

Michael Farrie, Bridgeport Town, Bridge County, Juras, Little Neston, drawing, 2020

Welcome to Bridge County, we are an intensely urban and industrial outlier to the capital city of Station in the country of Juras, with industry that makes the most of the renewable energy from the Bridge Bay, home to well over 100,000 inhabitants who are served by the local hit music station Bridge County FM.

Rafael Guendelman Hales

Rafael Guendelman Hales, A crack in history, Santiago, Chile, drawing, 2020

'In the place where Neoliberalism was born, is where it is going to die' it says in some street wall painting in Valparaiso, a city in Chile next to the Pacific Ocean where graffiti and lost cats are everywhere. A city without rules, a space of chaos in this very ruled country. Since last October we are living our own historical process. The system collapsed and the people can’t handle the illusion of being ok. We are not well. Our (and your) system is not an option anymore. Rodrigo Karmy said that revolts are the moment when the flow of time is paused and society (the people) can think their own present, their own destiny. A crack in history to redraw our small world (together, I hope).

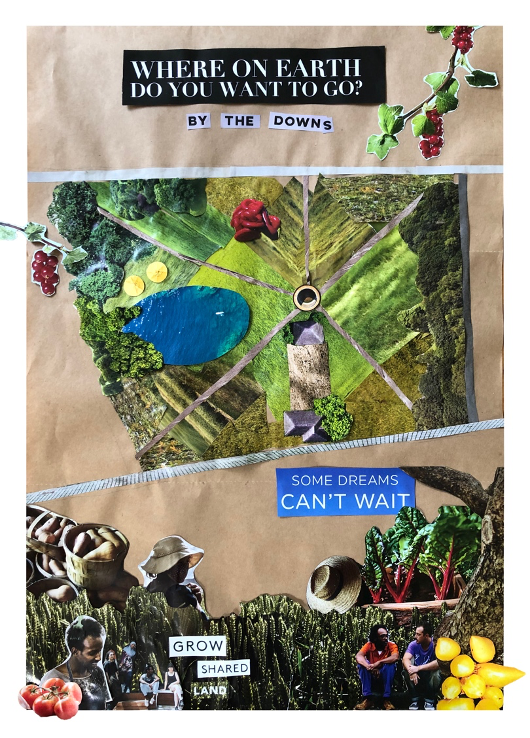

Sol Perez-Martinez

Sol Perez-Martinez, Hackney Downs Park Allotment, London, UK, collage, 2020

During lockdown I regularly thought about food security and growing plants as a mental health strategy. Given the lack of outdoor space to grow vegetables in my flat, I started looking for an adequate spot in my neighbourhood to create an allotment. My collage advocates for a better use of certain abandoned parts of Hackney Down park and works as an invitation for the neighbours to imagine the possibilities of the park as a community space. It repurposes images from travel magazines to create a prefiguration of a world where we can share land, grow our food and develop stronger community bonds with our neighbours. All in close proximity of our homes.

Sophie Cunningham Dawe

Sophie Cunningham Dawe, Into the woods, Winchester, Spatial drawings with AR app and paper, 2020

This yew-lined holloway connects the ancient woodland site of a Roman villa to a more ancient ridgeway. Here, roman roads layer over ancient walking tracks, forming one of our national walking trails, the Monarch’s Way. I am seeking ancient yews, Britain’s oldest trees. The process of drawing while walking these paths focuses my mind through my body to the world and back to myself - a solitary, restorative strategy for navigating this pandemic. The resulting abstract amorphous drawings resist easy recognition. They seem to attempt an internal mapping of neural pathways and how ideas might take shape and float free.

Tadea de Ipiña Mariscal

Tadea de Ipiña Mariscal, Isolated worlds, Santiago, Chile, collage, 2020

The global message of being together to overcome this situation, and the feeling that we are all suffering the same loneliness and isolation, has triggered moments in which I have felt rather more united to people I know just superficially than to closer ones. After nine years away from my country, in these circumstances the family has learned to be close, while being far, no matter how many miles separated us. My tasks, both professional and personal make me see each piece separately, everyone seemed to live on a different planet, as if orbiting around the house, hardly meeting the others, surviving the pandemic on our own. After four months of confinement, all I appreciate is to see my children grow and the generation of a strong familiar union in spite of the tiredness it implied. I strongly reject the fact that in moments of crisis women somehow have returned to long forgotten former social positions.

Dreaming an ideal place

Dreaming of an imaginary world can give us comfort but can also help us clarify how we would like the world to be. According to sociologist Ruth Levitas the ‘construction of imaginary worlds, free from the difficulties that beset us in reality’ is a common feature of many cultures.[4] These ideal places, also called utopias, are present in religion, architecture, music, novels and maps. In popular culture, a utopia is a perfect society which is impossible to achieve, ‘either an idle dream’ or a ‘dangerous illusion’.[5] However, Levitas’s utopia also carries the longing for social change as 'the expression of a desire for a better way of living’.[6] The philosopher Ernst Bloch called this reaction a ‘utopian impulse’ and considered it ‘an intrinsic part of what it means to be human’.[7]

The term utopia was coined by Thomas More in his book of the same name in 1516 to refer to a non-existent place or society. In his fiction, More created a remote imaginary island with an ideal society as a response to the ills of his reality. Combining three Greek words, non (u), good (eu) and place (topos), utopia for More meant non-place and good-place, thus its connections to an ideal society with specific material characteristics.[8] More accompanied his text with an illustration of Utopia, a map which was the blueprint for his alternative society. For the literature scholar Jason Pearl, these maps or ‘utopian geographies’ were at the core of the first English novels and served as a vehicle for storytelling.[9] Since its creation, maps, storytelling and ideal places were closely connected.

‘Everyone has an ideal place. When you’re five it is probably the sweet counter at Woolworths; when you’re ten it might be a toyshop or the seaside on a summer day. But when you’re fifteen, twenty, thirty, fifty? The older you get, the more varied and complicated your version of an ideal place becomes. Is it an ideal place just for you, or your family or friends, or one which you want everyone to share?’[10]

In 1974, the British anarchist writer and urbanist Colin Ward published Utopia, a book for secondary students initially thought to ‘transform the teaching of geography for children aged eleven to fourteen’.[11] Through a series of images, songs and stories Ward presents a diverse set of imagined worlds, emphasising their connections to their creators and the real world. Ward starts by asking the reader ‘What is your ideal place? What would it be like there?’.[12] Similar to this call, he invites us to ‘write a description and draw, map or model before you go any further’.[13] Ward’s intention is twofold, firstly to offer a ‘Do-it-yourself-utopia-kit’ so young people could create their own utopias according to their dreams and desires; and secondly to teach the reader to critically examine the ideas behind these imagined worlds, a skill that they could later use to understand the real world.[14]

For Ward, imagined and real worlds were tightly connected and you could use one to understand the other. He writes ‘If you look carefully, you’ll find utopias always tell you something, often a great deal, about the people who thought of them. So do real places.’[15] Through radical references and first-hand experiences, this short publication shows how utopias are not just dreams but can also be paths for real change. This idea follows the anarchist tradition of creating ‘examples of future worlds’ as a way of bringing ‘Ideas to life’.[16] The sociologist Jeff Shantz calls these utopias ‘futures in present' and connects them to Michel Foucault’s ‘heterotopias’.[17] For Foucault, utopias are ‘sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society’.[18] According to Foucault, heterotopias are worlds within worlds, and in societies without them ‘dreams dry up’.[19]

With Utopia, Ward was proposing what sociologist Rhiannon Firth called a ‘utopian pedagogy’, a path to social change ‘based on the ability to transform individual consciousness through immanent practice and to transform society by means of examples’.[20] Ward was not waiting for an ‘instant utopia’ that would appear after a revolution, rather he advocated for practices ‘in the here and now… as seeds for a further future’.[21] By inviting people to think about their own ideal place, Ward is encouraging the reader to think of a new world in the shell of the old.[22] Similar to Ward, for political philosophers Benjamin Franks and Ruth Kinna, prefiguration fosters the idea that radical change does not come from a single revolutionary moment but it is a continuous process.[23] Ward guides the reader to ‘prefigure’ alternative relationships among the existing ones using texts, models and drawings as tools.

This open call is grounded on Ward’s ideas and proposes the use of maps as the prefiguration of an ideal world, either locally or beyond. Mapping our ideas of the future can operate as a way of escape or liberation, a starting point for new stories to tell. The American science fiction author, Ursula Le Guin, called this process imaginative fiction. For Le Guin ‘imaginative fiction trains people to be aware that there are other ways to do things, that there are other ways to be... it trains the imagination’.[24]By imagining ideal places we educate our imagination to think beyond our reality. Through mapping these ideas, we can communicate our dreams to others. But then, how do we illustrate the worlds we have created in our dreams?

Map making

Memories of a favourite place or the feelings that someone has towards a place are likely to be enveloped within many layers of personal meanings and associations. ‘Like memory, geography is associative’, places that we have been to become intertwined with memories of other places, fantasies and dreams.[25] The imagination, dreams and memory are subjective, they exist within the thoughts of the person who thinks them. They are notions, feelings and sensations that come about through lived experience. Making a map of a place is one way of tuning in to these experiences, and also a way of transforming them into something that can be seen or read by someone else.

Drawing a map of a familiar neighbourhood for instance, calls to mind the experiences of physically having been there. By drawing the position of a certain street, building, or tree onto a sheet of paper, the map maker takes an imaginary journey to that place with their mind’s eye, imagining themselves physically standing in front of it. As anthropologist Tim Ingold puts it, the line marked on a sketched map becomes ‘a path traced through the terrain of lived experience’.[26] The physical act of making marks on paper; drawing, cutting, sticking and collaging, gives a material and bodily perspective to something that exists as a primarily in-head experience. A handmade map is not simply a drawing of a place, but something that recalls a full-body experience. Similarly, a map of a place that does not exist in reality, i.e. one that exists purely in the imagination, embodies the map maker’s recollections of their own experiences of places that they have been, extrapolating elements from various places and pulling them together. Through this process, an imagined place can come into existence through the process of drawing or mapping.

To some extent all maps tell stories about places, they capture traces of moments in time, charting reality from particular perspectives. Maps that attempt to be more objective, such as those that tell us how to get from A-B can ignite an element of fantasy or dreaming in the mind of the viewer. We can look at a map of a place that we have never been and try to imagine ourselves being there. Handmade maps in particular, as map collector Katherine Harmon suggests, are ‘a vehicle for the imagination’.[27] From the perspective of a viewer, they offer a glimpse into another person’s world, but also enable the possibility to create, invent and imagine.

From the perspective of the map maker, the process of making a map can be a form of visual storytelling about a place. Map-making artist Jill Berry provides a methodological toolkit for mapping personal geographies.[28] She points out that maps of personal geographies do not have to be depictions of places with aerial views, streets and buildings, but can equally be abstract collections of lines and marks, ambiguous or poetic. Abstract maps could be depictions both of real and imagined places, abstract interpretations of internal landscapes, or poetic pictorial images of hopes and dreams. Map making, and mark making are flexible and fluid practices. There is no singular way of making a map, likewise, there is no singular way of interpreting one. Rather than striving for accuracy, or objectivity, our project highlights the power and beauty of subjectivity and the imagination Thinking with maps

We received contributions that varied greatly in technique, style and topic, but recurring themes and patterns emerged. These became clearer after a Livingmaps Network public event online on 22 July 2020 where all contributors were invited to present and discuss their ideas with an international audience. Following the event, we loosely categorised the maps into three thematic groups: Community action and political proposals, Re-reading reality, and Inner worlds. In this section we hope to establish connections between the call, the themes and the maps.

Community action and political proposals

Images in this section came in various forms, from literal to abstract, but all of them shared a desire for change. Similar to Colin Ward’s ‘Do-it-yourself-utopia’, these submissions reveal the concerns and aspirations of their authors for the world around them as well as the conflicts present in their places of confinement. As part of the more actionable proposals, Rafael Guendelman Hales’ vision of a utopian post-capitalist town depicts an imagined town square, reminiscent perhaps of a real town square in a real city somewhere, but simultaneously remote and surrounded by nature. The town comes complete with a ‘Decolonisation Ministry’, a ‘space for non-competitive friendships’, ‘a square for collective creativity’ as well as a ‘house for experimental meetings’. The new institutions proposed in Guendelman’s drawing are titled in English and Spanish, offering a shared world for these two languages. The lines are distorted and disappear in the corners of the image, reminding us that this representation remains a dream.

Andrew Howe’s map of Frankwell is a glimpse into an imagined, yet plausible, sustainable cultural centre for Shrewsbury. The map itself is literal and playful in its execution. He skilfully uses colour squares to indicate the land use without defining exactly their limits. Detailed requests appear in the form of text tags where he describes the type of spaces and activities he envisions. As a map it offers a clear proposal for a possible future, based on an existing geography. Likewise, Sol Perez-Martinez’s submission is a plan for change in a local park. Using collage, she presents her ideal version of Hackney Downs Park adding art works, water features, woodland areas and an allotment to the plan of the park, as a way of offering an alternative vision of the park as a community area. Repurposing the images and texts of travel magazines, she creates a parallel reality on her doorstep which is inclusive, diverse, and land-based. With her collage she advocates to shift the energy of travelling and exploring new places to community building and organising in the places we call home during lockdown.

Menekse Aydin’s bread map takes the notion of civics to a visceral level. Her bread map of the world is a reminder of the ephemerality of human existence and human constructs of borders and nations. As the bread disappears into someone's bodily system, so too do the borders of the world dissolve. Aydin explained during the online event that the type of bread she used for the map is a local Turkish pastry used in celebrations, making her map of the world a construction from a specific situated perspective. The seeds of the bread in the first image seem to represent people over the continental masses. In the last image only seeds are left floating in blank space, maybe as a suggestion that after the borders disappear we are all human with no divisions. Michael Farrie’s map appears at first glance to be a hand drawn version of a page from a city A-Z map, using a similar aesthetic and system of labelling. It seems plausible and real. In fact, Bridgeport is a fictional suburb of an imagined sustainable city, powered by renewable energy. This page is just one section of a street atlas of an entire imagined county. Farrie’s imagined world is set in a fictional utopian past in a technologically advanced modern society roughly around the year 1995. Along with the map, the imagined city has its own radio station - Bridgecounty FM, which can be listened to on Mixcloud. By listening to the radio, one could almost imagine themselves driving through this fictional town with the radio on. In a similarly line, the Di Parodi family uses drawing to embed their desires of a caring reality, full of colour and enjoyment represented in a concert attended by a diverse set of characters. The overlap of colours and shapes reminds us of the chaos brought by the global pandemic into family households, but this collective drawing offers a harmonic mix of all these forces into a single image. Different to other maps in this call, the Di Parodi map was a collaborative endeavour where the process of making the map between multiple members of the family is a political proposal in itself, the collective creation of an imagined world.

Re-reading reality

Whilst some maps suggested alternative futures, others were a reflection on the daily reality of the pandemic. Laurien Versteegh’s map is one of escape, a dream of getting out of the reality of quarantine. Her family had walked up and down the garden back and forth to a vegetable patch that they created an unintentional ode to Richard Long’s ‘A line made by walking’.[29] If only that line would keep growing deeper, and an escalator would appear to transport them out of the garden. Margaret Ramsay’s also focuses on the notion of travel and getting outside. The central motif of the map is a deconstructed bicycle, which not only highlights cycling as a sustainable and safe means of travelling during the pandemic, but also acts as a route into the drawing. The spokes of the wheels, brake cables and cut out sections of the frame become the roads and pathways of an imagined landscape. Joel Seath’s project presents us with the personal geographies of children through their own eyes. The maps themselves are drawings of their representations of places and things in their local landscapes that are important to them such as their homes, family, friends and nature, and particularly the things that are missing from their lives during the lockdown. The maps flicker between reality and fantasy with existing landmarks intertwined with imagined places. The maps are journeys through the children’s own worlds.

Crab Man’s sketch presents us with a moment in time, and a reflection on an unfolding reality towards the end of the lockdown period. He sits down to sketch the landscape in front of him, stopping to observe the landscape, just as lockdown itself became a time for pause and reflection for many. But he is soon forced to leave as the place where he is sitting soon becomes too crowded with people, just as the easing of lockdown was soon overtaken by the insistence of the capitalist machine to continue running. We are left wondering, is the sketch finished? Is a map ever complete or will it continue to evolve?

Inner worlds

The final category of works has a common notion of embodiment, where there is not a depiction of a landscape per se, but a relationship of the body to a landscape. These works are more abstract in nature, and deal with more fluid notions of time and space. Clare Qualmann’s sketch could be seen as a map of an internal landscape – it is a map of the connectivity of the body to the world and others around it. Her map is a zooming in, reflecting on the turn to the ‘super-local’ during lockdown and the impact that it has on daily reality, and to an even greater extent zooming in to the body itself and then even further to the microbial, and the molecular. The meshwork of interconnected lines and marks in her drawings offers the viewer pathways to follow, routes in and out. It is a way of reaching out to the world, attempting to reconnect after shrinking all the way inside.

Emma Fält is another example of an artist working with mark making. But where Qualmann’s marks are graphic and considered, and Linda Knight’s are sketchy and entangled, Fält’s are spontaneous and unexpected. She works with a marbling technique to generate flecks and blobs of ink on the paper. By working with the surface tension of the water and the resistance of the ink, she plays with a symbiotic relation between chaos and control. Letting go of control, and letting it flow, becomes a way for her to challenge her own expectations and fears. Embracing the new and unexpected is a way of embracing and accepting the changes and challenges in the current reality. Fält’s is a map of traces and chance encounters, where happy accidents offer glimmers of hope.

Knight’s abstract collection of marks gesturally allude to a microbial level. Her map is that of a body, an ‘inefficient mapping of a posthuman citizen’, permeated by chemicals, micro-organisms and viruses. The entanglement of lines in her drawing give a substance, albeit an imagined one, to visualise a cosmopolitical civics of urban life. It provokes a reflection on how as bodies, we live together, how we interact and how we communicate. Not only through words and relationships, but also how our molecular presence permeates the air and other people’s bodies.

Traces feature also in Sophie Cunningham-Dawe’s work. Her map is twofold, a drawn collection of lines on paper, as well as a three-dimensional VR drawing in space. Her map focuses on a specific place of both personal interest and historic significance: a hollow way which forms part of a Roman Dover’s path, the Clarendon Way. As she traces her meandering routes along this historic path both physically and digitally, she references the notion of the landscape as a palimpsest. A path which has been eroded by 2000 years of footsteps into the earth become marks etched on paper and digital marks whose traces can only be experienced virtually. Her drawings remind us that our presence within the scheme of history is fleeting, and that the landscape will continue with or without us. Tadea de Ipiña Mariscal’s collage represents a series of worlds. Her map is not a map of a place per se, but a pictorial representation of the self within an orbit of people, places and identities. Her collage reflects on and critiques the notion that in times of crisis society pushes women back into traditional roles. Her map plays with notions of distance and closeness, about feeling close to her family whilst they are physically far away, and connecting with people in her immediate surroundings, echoing perhaps Qualmann’s symbolic reaching out from an internal space to the external world. Finally, Kimbal Bumstead’s collage explores the idea of travelling to a place beyond the here and now. Via the process of collaging, he recreates a journey through a place which was out of reach, a memory of a place where he once lived. The act of travelling to that place in his mind, whilst physically mapping it out, was a comforting feeling despite the reality of not being able to go there physically.

Mapping as a tool to imagine social change

Through this open call and this curatorial project, we aimed to encourage people to map their dreams during lockdown as a way to find comfort, explore our desires and exercise our imagination for social change. The range of submissions in terms of format and themes was varied, yet they all shared a similar feeling: the need to find tools to overcome the difficulties exposed by the lockdown. Creating or representing the world through maps and drawings gave us an opportunity to reflect and share our ideas with others in a time where isolation is a challenging aspect of everyday life. Making maps provided a way of understanding feelings or ideas that felt hard to pin down. Sharing maps provided a way of communicating private thoughts or desires, creating a digital sense of community and shared concerns.

Mapping – a common practice across the world – presents a shared language where all the places or ideas mapped are equally important. The ideal worlds represented were highly situated to each of its authors, yet they express needs which cross boundaries and nations. We believe that with the implementation of new lockdowns worldwide, this short exercise can become a tool for others to explore their desires, exercise their imagination and plan their ideal places, not in a faraway future but embedded in the present.

Authors

Kimbal Quist Bumstead is an interdisciplinary artist based in London whose work spans painting, drawing, video and performance. He trained in Fine Art at the University of Leeds and the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, followed by a Masters degree in Performance and Theatre from Queen Mary University of London. His current project, unmapping, explores the poetic aspects of cartography and the relationships between landscapes and memory through the lens of subjectivity, fantasy and fiction. Kimbal’s artworks are represented at various London galleries including GX Gallery, Jane Newbery Gallery and Aeon gallery. He is an associate member of Livingmaps Network and is a freelance workshop leader.

Sol Perez-Martinez is a Chilean architect, researcher and curator based in London. Before researching in the UK, Sol lectured in Chile and ran an architectural practice where she and her firm partners developed public and private projects. Since 2013, Sol has collaborated with educators, artists and architects curating educational programs, conferences and exhibitions to widen participation in the built environment. Sol is a qualified architect, with master’s degrees in architecture and architectural history. Currently, she is a PhD candidate at the Bartlett School of Architecture and the Institute of Education (UCL) while working as a consultant in Chile and the UK.

References

[1] ‘Coronavirus Confirmed as Pandemic by World Health Organization’, BBC News, 11 March 2020, section World <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-51839944> [accessed 21 October 2020].

[2] Katharine Harmon, You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination, Illustrated Edition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2003).

[3] Text translated from Spanish

[4] Ruth Levitas, The Concept of Utopia (Peter Lang, 2010), p. 1.

[5] Ruth Levitas, ‘Introduction: The Elusive Idea of Utopia’, History of the Human Sciences, 16.1 (2003), 1–10 (p. 3) <https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695103016001002>.

[6] Levitas, ‘Introduction’, p. 4.

[7] Levitas, ‘Introduction’, p. 4.

[8] Jason H. Pearl, ‘Introduction’, in Utopian Geographies and the Early English Novel (University of Virginia Press, 2014), pp. 1–20 (p. 1) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zwcr8.4> [accessed 19 October 2020].

[9] Pearl, p. 8.

[10] Colin Ward, Utopia (Penguin, 1974), p. 7.

[11] Joanne Norcup, ‘Awkward Geographies? An Historical and Cultural Geography of the Journal Contemporary Issues in Geography and Education (CIGE) (1983-1991). PhD Thesis’ (University of Glasgow, 2015), p. 63 <http://theses.gla.ac.uk/6849/1/2015NorcupPhD.pdf>.

[12] Ward, p. 5.

[13] Ward, p. 5.

[14] Ward, p. 112.

[15] Ward, p. 9.

[16] Jeff Shantz, Constructive Anarchy: Building Infrastructures of Resistance (Routledge, 2016), p. 9.

[17] Shantz, p. 9.

[18] Michel Foucault and Jay Miskowiec, ‘Of Other Spaces’, Diacritics, 16.1 (1986), 22–27 (p. 3) <https://doi.org/10.2307/464648>.

[19] Foucault and Miskowiec, p. 7.

[20] R. Firth, ‘Toward a Critical Utopian and Pedagogical Methodology’, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 35.4 (2013), 256–76 (p. 7).

[21] David Crouch, ‘Lived Spaces and Planning Anarchy: Theory and Practice of Colin Ward’, Planning Theory & Practice, 18.4 (2017), 684–89 (p. 686) <https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1371878>.

[22] Myrna Margulies Breitbart, ‘Looking Backward / Acting Forward’, Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, Special Issue, 44.5 (2012), 1579–1754 (p. 1582).

[23] Benjamin Franks and Ruth Kinna, ‘Contemporary British Anarchism’, Revue LISA / LISA e-Journal, vol. XII-n°8, p. 346 <https://www.academia.edu/14300337/Contemporary_British_Anarchism> [accessed 1 March 2020].

[24] The Worlds of Ursula K Le Guin <https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000bh0x/the-worlds-of-ursula-k-le-guin> [accessed 6 June 2020].

[25] Stephen S. Hall, ‘I, Mercator’, in You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination, by Katharine Harmon, Illustrated Edition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2003), pp. 15–35 (p. 15).

[26] Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (London?; New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 93.

[27] Harmon, p. 10.

[28] Jill K. Berry, Personal Geographies: Explorations in Mixed-Media Mapmaking, Illustrated Edition (Cincinnati, Ohio: North Light Books, 2011).

[29] Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967, Tate <https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/long-a-line-made-by-walking-p07149>.